A ‘carve-out’ exemption is unnecessarily broad and may result in manufacturers using it to prevent our right to repair many electronic devices.

by Anthony Rosborough, Alissa Centivany. Originally published on Policy Options

May 3, 2023

The federal government has made the “right to repair” a key policy priority, recognizing its importance in fostering a more sustainable and affordable future for all Canadians. Recent amendments to a bill before Parliament, however, threaten to jeopardize the government’s objectives.

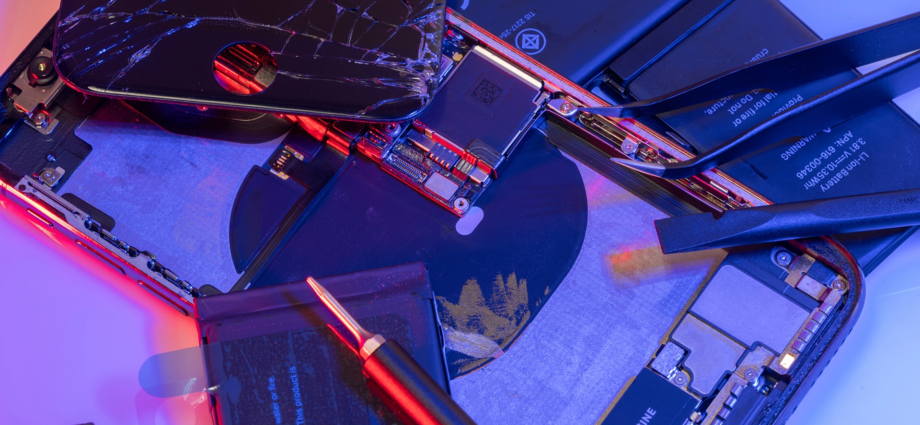

The “right to repair” is a social movement that seeks greater repairability of the products and devices around us – many of which have become unnecessarily difficult to fix. This difficulty is often the result of tactics by product manufacturers to control access to specialized parts, diagnostic information and special tools needed to complete repairs.

In the lead-up to the 2021 federal election, the Liberal Party promised “a right to repair your home appliances,” including amendments to the Copyright Act to ensure that manufacturers cannot use software copyright and digital locks to prevent the repair of digital devices and appliances. This commitment was solidified in the 2023 federal budget, where the government committed to implementing a right to repair, “with the aim of introducing a targeted framework for home appliances and electronics in 2024.”

Forming a key part that framework is Bill C-244, a private member’s bill introduced by Liberal MP Wilson Miao (Richmond Centre) in February, 2022. The bill targets digital locks, or “technological protection measures,” under the Copyright Act. Digital locks are encryption, passwords or other mechanisms used to protect copyrighted works.

Digital locks originated as copy-control mechanisms for physical media such as digital audio tapes and CDs at the turn of the millennium. They were incorporated into the Copyright Act in 2011 amid considerable scrutiny and criticism. They have since evolved into tools that prevent access to software in computerized devices and systems, regardless of whether any infringement or unauthorized copying has taken place.

This has given device manufacturers an unprecedented amount of power in deciding the terms and costs of diagnosing and completing repairs to computerized devices. As more and more of the products and connected devices we buy rely on embedded computer systems, the more wide-reaching this power gets – home appliances, agricultural equipment, electric vehicles, medical equipment, personal computers, and the list goes on.

Bill C-244 proposes an exemption to Canada’s rules on digital locks to make it lawful to circumvent or bypass these protections where the sole purpose is for “diagnosing or repairing a product.” The bill has been lauded by repair advocates for its potential to give independent repair technicians the latitude to complete repairs without the fear of huge civil and criminal penalties for unauthorized circumvention. These reforms may also give provinces the breathing room needed to enact important amendments to consumer protection statutes without fear of encroaching on the federal government’s jurisdiction over intellectual property.

But a recent amendment to the bill risks leaving it without much reason for optimism. In a meeting of the standing committee on industry and technology on late March, members agreed to amend Bill C-244 to create a “carve-out” for devices with embedded sound recordings. In other words, it’s an exemption to Bill C-244’s exception. There is very little information on the reasons for this amendment and almost no discussion took place before it was adopted.

While seemingly harmless at first blush, this caveat may serve as a powerful loophole for manufacturers. The most obvious devices to which this would apply are those primarily used for playing music, but the amendment to the bill is broad enough that it could be stretched much further.

We can only speculate, but the amendment appears to protect the interests of “content industries” – music, film, gaming – as well as those industries unrelated to the production of creative content and digital media. In theory, the exemption in the amendment would prevent circumvention of digital locks in devices where software controls access to musical works.

For example, this could be a digital lock in your smartphone that prevents you from accessing the music audio files used by a streaming app like Spotify. A charitable view of this exemption is that it would safeguard against copyright infringement where a user bypasses a digital lock and then copies music or audio files.

But a less charitable view is that it gives manufacturers another tool to prevent access to repair. We already have clothes dryers, electric kettles and toilets that play jingles as part of their normal operation. With this exemption to the exception, we can envision manufacturers embedding musicality into an even wider range of products – tractors, toasters, wheelchairs – to take advantage of this carve-out for sound recordings. After all, manufacturers co-opting copyright law to restrict repair is a big part of the reason we are in this mess.

Beyond the potential to dilute the impact of Bill C-244, the amendment also speaks to a larger concern about copyright and intellectual property policy. Carving out exceptions for specific industries is difficult to justify in the context of the Copyright Act. It is not clear why devices with embedded sound recordings should be treated any differently than any other type of device when it comes to repair or diagnosis. As drafted, the bill already made clear that any activities that constitute copyright infringement are not within the scope of “repair.” This leaves little reason to single out devices with embedded musical works other than to create a loophole for abuse by manufacturers.

Prohibiting infringement or unauthorized distribution of music, which the Copyright Act already does, ought to be enough. Through a 30-year war on digital formats and devices, the content industries have been the principal architects of digital locks. We have seen the lengths that the recording and content industries will go to lock down technologies, starting with the digital audio tape (DAT) format in the 1980s, copy protection on music CDs that secretly installed viruses on people’s home computers, and the use of digital locks on iPods, iPhones and other portable media players beginning in the early 2000s.

History shows us that where copyright law leaves an opportunity for technology manufacturers to lockdown the devices they produce, they take it. The public interest will be impaired if we allow digital locks – a relic of copyright law intended to curtail digital and online infringement – to restrict socially, environmental and economically beneficial activities such as repair, particularly when it comes to products and devices like farming equipment or medical devices. Importantly, these devices are not primarily intended to embody music or other copyright works in the first place.

Canada should applaud the effort and spirit behind Bill C-244. The bill offers much hope. If the government is serious about achieving its campaign promises and budgetary goals, it ought to think twice about including industry-specific carve-outs that leave so much room for abuse.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

This article first appeared on Policy Options and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.