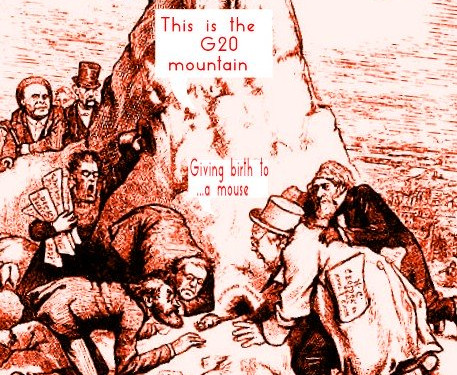

The surprise issuing of the Leaders’ Declaration a day early and a new $20 billion infrastructure project do not change the fact that despite India’s commendable efforts, the Summit is like the proverbial mountain that labored and brought forth a mouse: it has no structural capacity for serious decision-making

by Claude Forthomme – Senior Editor

September 12,2023

Updated September 10, 2023: The two-day G20 Summit that started in India on September 9 delivered a big surprise: For the first time, the Leaders’ Declaration (the final communiqué) was issued not at the close of the meeting but a day early, with predictably, a series of rousing “commitments” everyone could endorse (incidentally, in relation to the war in Ukraine, there was no blame on Russia). And at the press conference, there was a juicy $20 billion offer on the table:

The leaders of the USA, India, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates announced a major joint infrastructure deal to connect Gulf and Arab countries via a network of railways.

The advantage of doing a surprise announcement full of good cheer is obvious: It makes everyone forget what just a few days ago was the “talk of the town”: the failure of Russia and China’s leaders to turn up. And reportedly, Putin didn’t even prepare a video address (as he did for the BRICS Summit in South Africa).

It also buries problems – not least of them, the War in Ukraine – that have beset this G20 meeting and its preparation this year. Because, so far, we’d had nothing but uninspiring news about all the ministerial preparatory meetings leading up to the G20.

And this is not surprising: Bottom line, the G20 lacks the structural capacity for serious decision-making, that is: decisions that address the main issues of the day -in this case the destruction of our planet – and are followed by action.

As Impakter reported in July, the G20 energy ministers failed to endorse ambitious renewable energy targets or agree on phasing out fossil fuels. Likewise, the G20 finance ministers and central bank governors were unable to reach an agreement on debt restructuring, leaving low-income countries without a solution.

In August, the G20 environment and climate ministers recommitted to the Paris Climate Agreement in an outcome document, sounding all the right words – “note the importance”, “endorse”, “support”, “promote”, “enhance efforts”, “scale up efforts”, “commit to address”, “resolve to pursue environmentally sustainable and inclusive economic growth and development” etc, etc. – which made them sound like they were writing a letter to Father Christmas.

But they showed their true colors when they came to a so-called “agreement on Blue Economy principles” (9 principles no less) stating (in an annex to the document, presumably to ensure low visibility), that the said principles “may be implemented by the G20 members on a voluntary basis, based on national circumstances and priorities.”

Yes, voluntary – meaning you do as you like and in any case, your national priorities trump world issues – like climate change or biodiversity loss – every time, no problem.

So one may well ask: What use is the G20 if it doesn’t push forward on the most pressing issues?

It’s been around now for 24 years (since 1999) and it brings together the world’s most important countries – 19 plus the EU – representing 85 percent of the global GDP, 75 percent of international trade, and two-thirds of the world population. And what has it got to show for it?

G20 participants have no doubts about the usefulness of the G20. India, the host country this year, officially defines it as the “premier intergovernmental forum for international economic cooperation.”

A “premier forum”? Probably – although, arguably, the premier forum for international cooperation is not the G20 but the United Nations in general and the IMF in particular.

And India has set an agenda for the meeting that rings all the right bells, giving it a suitably Indian-sounding theme:

“VasudhaivaKutumbakam” or “One Earth . One Family . One Future”

Nice and cozy and if you think about it, what lies at the center of this is…sustainability (of course!).

Washington was quick to build on it and came up with its own list of related topics for discussion:

- the clean energy transition and combatting climate change

- increasing the capacity of multilateral development banks, including the World Bank, to better fight poverty, including by addressing global challenges

- mitigating the economic and social impacts of Putin’s war in Ukraine

And there you have it, out in the open, the skeleton in the closet, or better yet, the elephant in the room: The war in Ukraine. Clearly, not a subject for “international economic cooperation” but one for political cooperation – and that, in principle, is not the business of the G20 but of the UN Security Council, which, as we all know, is paralyzed by the veto power of Russia, a permanent member of the Council, one of five (the others are the US, China, the UK, and France).

Needless to say, until the world fixes that problem, we are without a mechanism to maintain world peace, and the G20 cannot be that fix.

Why the G20 is powerless: Hobbled by big power rivalries plus a structural weakness

There are several reasons why the G20 is powerless and all of them are the same ones that make BRICS an international weakling (unless and until some restructuring is done to turn it into a “real” international organization).

First, as I explained in a recent article summing up the lack of results from the BRICS recent summit, big power rivalries are hobbling them.

What doesn’t work for BRICS won’t work for the G20 either. And even if there’s now some excited talk of the G20 becoming the G21 with the addition of the African Union (AU), it won’t change anything to the fundamental weakness of the system.

India and China do not see eye-to-eye and are not going to resolve their problems at the G20; attempts by the West to dominate discussions are unwelcome by the rest of the G20 members; attempts by China to propose an alternative fizzle out as countries realize that they will only sink deeper in debt, yoking themselves to China for good (and bad).

I could go on and on listing the political problems, but at this coming meeting, it’s the War in Ukraine that is going to be the top stumbling block: We need to remember that China has always maintained special (call them close) relations with Russia. At the same time, the West has unleashed a wide range of sanctions against Russia that nobody appreciates either in China or in several other big players in the Global South (like India). Not to mention the usual culprits like Iran, North Korea or Cuba who are staunch supporters of Russia (but not members of the G20).

Second, there’s a deeper, more permanent flaw that the G20 can never fix and that explains why it is destined to remain powerless: It’s a debate forum, not a decision-making one.

That’s because the G20 was poorly conceived from the start, as a mere “intergovernmental forum” and not as an international organization – with the emphasis on the word “forum”: a place to talk about issues, and “talk” is the operative word here.

Unlike the UN which is a true international organization, the G20 has no permanent secretariat or staff and this means that the agenda is necessarily a moveable feast.

The biggest issues of the day do make it into the agenda, and for a while, the host country’s ministries – finance, health, environment, agriculture etc. – do work together on the issues.But then the chair goes to the next country and a new batch of bureaucrats steps in. And it all starts all over again.

The dialogue established between ministries is no doubt helpful – to a degree (more about that below). But the problem of a lack of continuity remains intact despite the “Troika” system in place. That term refers to the fact that a host country is helped along by the “sherpas” (appointed senior officials representing leaders) from the country that chaired the previous Summit and the one after. In the case of India, this means Indonesia (the host in 2022) and Brazil (to chair in 2024).

Consider the current political situation:

- With the ongoing war in Ukraine, how likely is it that American or EU bureaucrats are “working together” with Russians on that topic? That is a distinct advantage of the UN: Having an international staff that is “neutral” by definition;

- How can this kind of presidential “musical chairs” ensure any kind of continuity in policies and actions – assuming some serious decision-making does take place?

But of course, “serious” decisions that are followed by action are highly unlikely. What we see are declarations of support for highly laudable goals but no genuine commitment sinceeverything is “voluntary”.

No question: “National priorities” are always going to be more important than international ones – such as fighting plastic pollution or solving the debt problem of poor countries (one of the best and quickest ways to help them climb out of poverty). But then, for G20 leaders, the national level is where everything that matters politically happens and that is not likely to change anytime soon.

One positive G20 innovation: A modus operandi that contributes to international cooperation

Does that mean the G20 with all its expenses is a waste of time and money? There’s a silver lining: The G20 has done something for international cooperation that the UN has never done. It has brought together – on a rotating basis – the senior bureaucrats (and their staff) from every G20 member major ministry (finance, health, environment, etc.) People who have never left their own country learn to speak to their counterparts in other countries, shaping discussions and focusing on the major global topics of the moment.

That experience is unique to an “international forum” like the G20 and also the G7 – not the case with the United Nations or any other international organization (like the World Bank, IMF, Asian Development Bank, etc.). that has its own permanent staff. There, the dialogue with member countries takes place through “official channels” and at conferences, i.e. diplomats and/or spokespersons from the concerned national ministries (e.g. from the finance ministry for the IMF, agriculture for the FAO, etc.).

That dialogue through “official channels” leaves international organizations like the UN in a fairly isolated place, often functioning on their own (which has its own advantage as the UN is an environment where new ideas can be more freely embraced, especially among the lower, more “technical” levels of the secretariat). But the “working together” experience that the G20 offers (and to a lesser degree, the G7) is invaluable: It broadens the outlook of bureaucrats who otherwise would remain enclosed in narrow national perspectives, blind to other points of view.

The G20 cooperation mechanism should be put to better use

That particular dialogue at the level of national ministries – a modus operandi that is continuous and lasts several months – is an entirely new mechanism of cooperation that the G20 and G7 have brought to the international table. A mechanism the UN should consider integrating in its own methods of work. Alternatively, some formula for closer links with the UN could be considered.

For now, all that happens is that the conclusions of G20 meetings are closely watched by the UN secretariat as they give an early indication of what positions those major G20 countries will take when they speak in UN fora.

And because of the need to reach a consensus to produce the final communiqué, in a situation of extreme rivalry and political competition such as exists within the G20, the conclusions and recommendations will necessarily be at the level of the lowest common denominator. This coming weekend, we can be certain that we’ll see once again…a pretty mouse.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

This article was originally published on IMPAKTER. Read the original article.