Steven W. Kerrigan, RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences

May 15, 2025

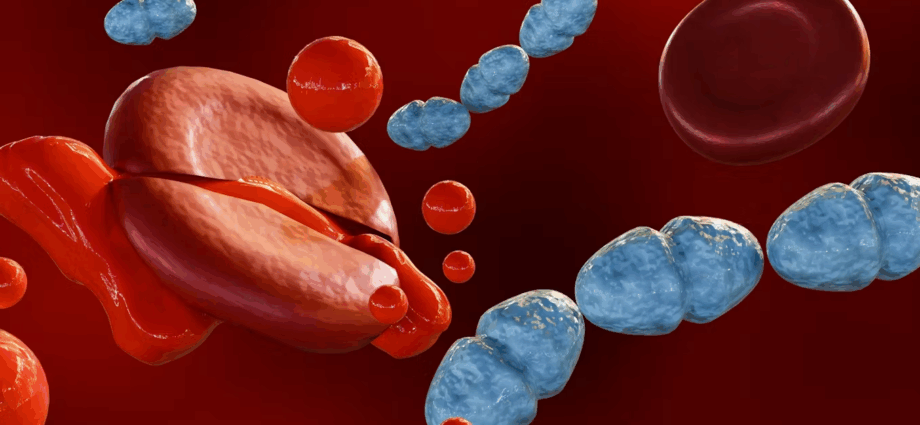

Sepsis is a life-threatening condition triggered by the body’s extreme response to infection. It causes widespread inflammation, which can lead to tissue damage, organ failure and death.

Thanks to modern medicine, survival rates have improved dramatically. But for many who survive, the battle isn’t over when they leave hospital. Instead, they enter a new and often overlooked phase of recovery marked by lingering, life-altering effects.

Post-sepsis syndrome (PSS) affects up to half of all sepsis survivors and can persist for months or even years. It’s a complex mix of physical, cognitive and psychological symptoms. People may seem physically recovered yet struggle with overwhelming fatigue, chronic pain, muscle weakness and disrupted sleep.

The most profound impacts, however, often show up in the brain. Many sepsis survivors experience cognitive problems that mirror those seen in traumatic brain injury or early dementia. These can include memory lapses, difficulty concentrating, slower thinking and impaired decision-making.

For some, these challenges are manageable. For others, they’re severe enough to interfere with work, education or independent living.

One major culprit appears to be the body’s own inflammatory response. During sepsis, the immune system floods the body with inflammatory molecules – a so-called “cytokine storm”. This can damage the blood-brain barrier, allowing harmful substances and immune cells into the brain. The resulting neuroinflammation and oxygen deprivation can injure brain cells and disrupt normal function.

Hidden psychological toll

Anyone who survives sepsis can develop PSS, but some are more vulnerable than others. Risk factors include: older age, which increases the likelihood of cognitive decline; long ICU stays or the use of a ventilator, which can contribute to physical and mental complications; pre-existing mental health or cognitive conditions; and more severe inflammatory responses during sepsis, which are linked to lasting damage.

Children are also at risk, as they may experience developmental or emotional challenges that affect their learning and social development for years.

Many sepsis survivors go on to experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety or depression. These issues can be triggered by the trauma of a near-death experience, prolonged sedation, invasive treatments, or time spent in intensive care units (ICUs) – often while cut off from family and friends.

In fact, “ICU delirium”, which affects up to 80% of patients on ventilators, has been strongly associated with long-term cognitive and psychological impairment. Sepsis survivors who experience this often recall vivid, terrifying hallucinations during their ICU stay. These memories can haunt them more than the physical illness itself.

The recovery gap

One of the biggest challenges for sepsis survivors is the lack of follow-up care. Unlike heart attack or stroke recovery, which typically involves coordinated rehabilitation, post-sepsis care is often fragmented. Patients can be discharged without a recovery plan and left to navigate a confusing and lonely road back to health.

What’s needed are multidisciplinary post-sepsis clinics, where patients can access neurologists, psychologists, rehab specialists and social workers all under one roof. Early support, both psychological and cognitive, can dramatically improve long-term outcomes.

Sepsis doesn’t just take a toll on survivors – it affects families, communities and healthcare systems. Many survivors cannot return to work, require ongoing care, and face financial hardship. In the US, sepsis costs an estimated US$60 billion annually (£50.8 billion), much of it spent on post-acute care and readmissions.

There’s also a growing concern that sepsis may raise the risk of long-term neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s. More research is needed, but the links between inflammation, brain damage and cognitive decline are becoming harder to ignore.

Globally, there is progress in helping people survive sepsis. But we must also ensure that sepsis survivors thrive afterwards.

Here’s what I believe needs to happen now: encourage greater awareness of PSS among clinicians, patients and families; integrate post-sepsis care into chronic disease and rehabilitation programs; and generate more funding to research how and why PSS develops – and how to prevent or treat it.

People recovering from sepsis often rely heavily on loved ones who need better support themselves. Survivors also need clearer, kinder help to get back to work and school, or just back to the everyday routines that once felt normal.

Surviving sepsis is a triumph of modern medicine – but what comes after is still a neglected frontier. For too many, life after sepsis means battling invisible wounds that affect the brain, body and soul. Recognising, researching and responding to PSS isn’t just a clinical need – it’s a moral obligation. Survivors deserve more than survival. They deserve a chance to truly recover.

Steven W. Kerrigan, Professor of Precision Therapeutics, School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences, RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences

Subscribe to our newsletter.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.