Popular climate change documentaries often privilege wealthier countries and offer unbalanced coverage

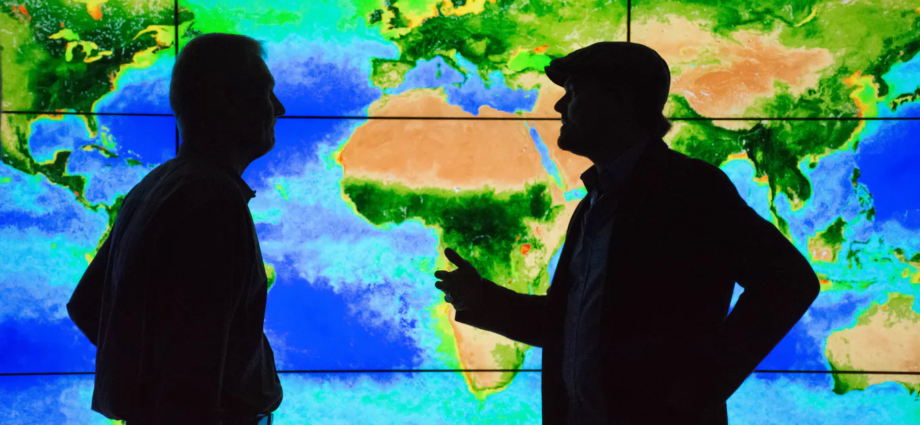

Leonardo DiCaprio, right, speaks with Earth scientist and deputy director of NASA’s Goddard Sciences and Exploration Directorate, Piers Sellers, for the climate change documentary, ‘Before the Flood.’ (Flickr/NASA Goddard Space Flight Center), CC BY-SA

Reuben Rose-Redwood, University of Victoria and Paige Bennett, University of Victoria

October 25, 2021

When world leaders meet in Glasgow, Scotland, for the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) this November, climate change will again be in the spotlight.

Media coverage of climate change plays an important role in shaping the public narrative on the climate crisis. In his book, Who Speaks for the Climate? Making Sense of Media Reporting on Climate Change, environmental studies researcher Maxwell Boykoff observes that “media representations of climate change are produced, negotiated and disseminated through unequal power and inequalities of access and resources.”

For example, The Associated Press drew criticism for cropping Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate out of a group photo at the World Economic Forum in 2020 to centre four white youth activists, including Greta Thunberg.

In response to the controversy, Nakate observed that her experience was part of a larger pattern where mainstream media rarely gives individuals from countries facing the worst impacts of climate change an opportunity to tell their stories.

In January 2020, Ugandan Climate Activist, Vanessa Nakate was cropped out of a photo she was in with her white peers by the Associated Press (AP).#BlackLivesMattters pic.twitter.com/vIJ15qPZrQ

— Daily World Chronicle (@DWorldChronicle) June 6, 2020

One form of media that is becoming increasingly popular is the climate change documentary. Documentaries tell powerful stories in engaging ways and often feature popular celebrities in order to bring star power to important issues. Even though these films reach large audiences, there have been few studies that examine the narratives they create, and how they do so.

Narrating the climate crisis in documentary films

In a recent study, we examined 10 climate change documentaries that have emerged since the release of Al Gore’s award-winning and genre-shaping film An Inconvenient Truth in 2006.

To understand how the story of climate change is told in popular documentaries, we selected films focusing on the climate crisis. Some of the criteria determining which films we chose included: films produced in English between 2006 and 2019; films released in a form that allowed widespread viewership such as theatrical release, screening on a major television network or availability on popular streaming platforms such as Netflix; and films that looked at climate change on a global scale and portrayed multiple geographic regions.

Most climate change documentaries we studied follow a similar formula: a central narrator — who is usually white and male — learns about climate change alongside the viewer, meeting people around the world.

Of the 10 narrators in the films we studied, only one, Naomi Klein in This Changes Everything, is female, and only one film, Time to Choose, is narrated by a racialized person. Eight of the 10 films are narrated by white men from the Global North.

It is common for documentaries to establish the science behind climate change by interviewing “global” scientific experts who can speak to its impacts. Of the individuals who fit this description, 75 per cent of speakers were white men (predominantly American or British), while less than one per cent of non-local scientific experts interviewed in the films we examined were racialized women.

By contrast, 76 per cent of those portrayed in the films as “victims” of the negative effects of climate change were racialized people. This alone is not unexpected, since the effects of climate change are felt unequally.

Black and Indigenous communities and people of colour have generally experienced the worst impacts of climate change in both the Global North and South.

However, the common pattern of contrasting racialized people who are affected with the almost exclusively white male “expert” reinforces racial and gender hierarchies of knowledge related to climate change. In this framing, white western experts are portrayed as those who understand climate change, while the solutions and knowledge of racialized groups are relegated to the margins.

Geographical disparities in screen-time

There is also a disparity in which regions are shown on screen and how they are portrayed in the climate change documentaries we analyzed.

Across the 10 films, North America received the most screen-time of any geographic region (19.5 per cent), followed by Asia (13.9 per cent) and Europe (7.2 per cent).

In the films we examined, three regions were repeatedly portrayed as uniquely vulnerable to climate change: the African continent, polar regions and small island nations. Despite their vulnerability, these regions received far less screen-time than other regions in the films.

When these regions were discussed, the majority of this footage focused on climate change impacts or how climate refugees would affect the Global North. This differs from portrayals of countries such as the United States or China, which focused on climate change causes, impacts and proposed solutions within each country.

While vulnerable regions are experiencing the accelerated impacts of climate change, using the limited screen-time available in this way reinforces existing one-dimensional media stereotypes and treats vulnerable regions as a means to the end of protecting the interests of wealthier countries.

Social stereotypes, unbalanced geographic coverage

Although the science of climate change is well-established, the way filmmakers frame scientific knowledge for public consumption in climate change documentaries with a global focus often reinforces social stereotypes and unbalanced coverage of the geographic regions most affected.

Some of the films we analyzed do challenge those stereotypes. This Changes Everything and How to Let Go of the World and Love All the Things Climate Can’t Change both include strong representation of Black, Indigenous and people of colour’s voices from around the world, while also being highly critical of the fossil fuel industry and inaction by western nations on climate change. Examples include featuring solar power at the Northern Cheyenne reservation in This Changes Everything, and the intimate portrait of a leader within the Pacific Climate Warriors’ fight against Australian coal in How to Let Go.

Challenging stereotypes

Our study focused on how documentaries on popular platforms with a global focus portrayed the climate crisis, which enabled us to compare representations of different geographic regions.

We also note that films with a more specific geographical focus that mobilize place-based knowledge can offer critical perspectives about climate change, and also push back against the imbalances and stereotypes we documented. One example is Qapirangajuq: Inuit Knowledge and Climate Change, an Inuktitut documentary with English (or French) subtitles co-directed by Inuk director Zacharias Kunuk.

This film, for example, provides a useful counterpoint to the popular climate change documentaries examined in our study, and suggests how Inuit, Indigenous or other local knowledges can contribute to our understanding of climate change.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

As the world turns its attention to the media coverage of COP26 in Glasgow, it is important to consider whose voices we focus on, who is on the periphery and who has been removed from the frame entirely in media narratives of the climate crisis.

Reuben Rose-Redwood, Associate Dean Academic in the Faculty of Social Sciences and Professor of Geography, University of Victoria and Paige Bennett, Affiliated Member, Critical Geographies Research Collaboratory, University of Victoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.