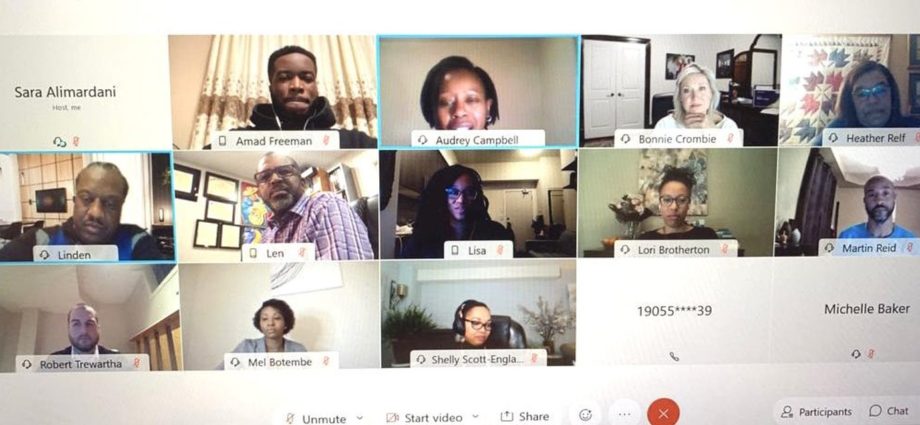

Crombie’s Black caucus. Photo from Twitter-Bonnie Crombie

By Isaac Callan, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, The Pointer

March 30, 2021

For one of the most diverse cities in the world, where almost two-thirds of residents are not white, Mississauga’s elected municipal officials offer a picture of political misrepresentation.

Only one member is a visible minority, the other eleven are white.

There is not one Black councillor.

This is a problem, and while promises to eradicate the barriers many Black residents face daily in the city have been made, there is no one with the lived experience to pull Mississauga’s decision makers out from the past.

In June, thousands of black squares began appearing on people’s Instagram feeds. Each was posted with the caption #blackouttuesday, designed to draw attention to conversations taking place around anti-Black racism following the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

The tiles were shared across Instagram and replaced the usual holiday snaps, makeup promotions or pictures of food. Acting almost as online art, it had a powerful visual impact.

But few who posted the black tiles took other meaningful actions. Critics were quick to suggest donations to relevant charities or calling out discriminatory behaviour in the real world would bring greater change. Well intentioned as they were, the thousands of black squares were performative.

One prominent Peel Region anti-racism group is concerned that promises to combat racism made by Mississauga Mayor Bonnie Crombie and the council she heads are equally ineffective.

The group, Advocacy Peel, was at the forefront of actions that forced change at the Peel District School Board, waging a relentless campaign to hold trustees and the board accountable for decades of support for a system that was admittedly harming Black and other visible minority students. The group’s unflinching mission cut through all the rhetoric and lip service used to mollify communities since the ‘80s. Polite complaints and cooperation had yielded few results.

Black and other visible minority teachers had been shut out from jobs and a board whose visible minority pupils made up almost 85 percent of the student body utterly failed to reflect them in the teaching and administrative ranks, which remain overwhelmingly white.

The group’s determination and surgical takedown of those who had helped protect racist policies and practices was not met with cooperation by the old guard who flailed away to protect the establishment.

Former Peel District School Board director of education, Peter Joshua, was even part of legal action by the board last year that aimed to unmask the crusaders behind Advocacy Peel’s social media activity so they could be served with libel notices. The group had been particularly vocal on Twitter, naming various trustees and staff members for actions it called out as anti-Black racism.

In the end, Advocacy Peel was armed with reams of data, other evidence and a scathing report produced by the Province that revealed the debilitating harm the board had inflicted upon Black students and families for decades.

Days after news of Joshua’s latest effort to silence the board’s critics broke, he was dismissed and the vindictive legal action was dropped.

Recently, Minister of Education Stephen Lecce joined a Zoom event organized by Advocacy Peel to mark one year since the Province released its deeply troubling review of PDSB, which led to the appointment of a provincial supervisor to take over governance of the dysfunctional board. Lecce’s appearance solidified Advocacy Peel’s status as a prominent anti-racism force in the region.

So when Kola Iluyomade, the founder of Advocacy Peel and a Mississauga resident, was told by Crombie to apply to join her Black Caucus, he expected to have a seat with his name on it. Instead, he was told there was no space for him in the group of 12 Black community members established to advise the mayor, some of whom are not from Mississauga.

Crombie’s office says she received around 20 applications to join the caucus.

“The mayor doesn’t want to disrupt,” Iluyomade told The Pointer. “There are people who are not residents of Mississauga on it, which tells you that’s rubbish.”

A spokesperson for the mayor confirmed the group was not entirely filled with Mississauga residents and agreed Crombie did suggest Advocacy Peel join the group. “After a list of names was assembled, the Mayor and Ms. [Sara] Almardani [senior advisor, stakeholder relations] assessed the list, with a key focus on ensuring they picked community members with a wide range of lived experiences, and who could represent the diverse perspectives of the Black community,” the mayor’s spokesperson said.

The Black Caucus itself exists in a grey area. It is not officially a committee and is not a function of council, meaning the mayor’s office has ultimate authority over who can sit around the table. Muddying the waters is the fact Crombie chose to make its creation a major publicity point in the summer, when the Black Lives Matter protests were at their height.

A lengthy summer motion introduced by Crombie declared anti-Black racism “a crisis” in Mississauga, established the Caucus through unanimous council approval, making it more than just a platform from where Crombie can quietly solicit advice. The motion also stated the lack of voices to speak on behalf of Black communities and the deteriorating conditions they face “requires immediate and sustained attention” in Mississauga.

A press release accompanied the adoption of the motion, proudly declaring: “Mississauga City Council stands against anti-Black racism, systemic racism and discrimination”.

The Black Caucus that emerged, officially under the purview of the mayor, is now under scrutiny. Civil rights leaders since the ‘60s, here and in the U.S., have made clear that one of the biggest barriers to progress is in the form of groups and campaigns hijacked by those more interested in preserving the status quo for their own benefit, rather than real change to transform our society.

The group will not release its minutes publicly, nor are its meetings available for residents to view. “This is not an official committee of the City but an advisory to the Mayor,” the spokesperson added. “Conversations are confidential in order to freely discuss items. Outcomes and recommendations will be presented to Council as part of the report back process on Motion 207.”

Examples offered of discussions so far include: the need for diversity and inclusion training for the City’s HR department; changes to the hiring process; structuring public feedback sessions with the community; and programming for Black History Month.

Despite the publicity drive around the adoption of Crombie’s motion, its progress has been slow. Unprompted public statements around its reporting and progress have been rare.

The mayor’s summer motion resolved to update the terms of reference for the City’s Diversity and Inclusion Committee (DIAC). The committee has faded in recent years, meeting rarely between 2014 and 2020, with the mayor herself absent from several meetings due to “scheduling” issues.

Nine months after the motion was adopted, DIAC, whose two white council leaders last year accepted criticism for the committee’s lack of focus and poor record of achievement, still seems to be floundering. The mayor’s office says this is because the City is in the process of hiring a Diversity and Inclusion Strategic Leader to work under City Manager, Paul Mitcham.

While DIAC remains unchanged, the Caucus is now up and running, slightly behind schedule. The motion that established the group said it was set to “report back to Council” in six months.

On November 24, the six-month mark passed, without even a meeting. Six days later, on November 30, the Caucus met for the first time. To date, it has held two meetings — the group is meant to meet every four-to-six weeks, according to the mayor’s office. Email communication has also taken place, according to Crombie’s office.

“She doesn’t want voices like mine because I will ask questions, I know particular statistics to ask for, data to ask for, evidence to ask for,” Iluyomade said. “It’s an illusion of power. They will give you access, but access is not power.”

Iluyomade is particularly concerned the mayor’s office will set an agenda that does not seek meaningful change, the type of transformation that creates opportunities for those who have been shut out from decision making and the very system of local government. “The mayor’s staff will be responsible to facilitate meetings and set agenda for meetings in consultation with the Mayor, the chair and/or members of the Black Caucus,” the group’s terms of reference state.

“It’s going to be issues that are impacting the community,” Black Caucus Chair Linden King, who also sits on similar groups with the Peel Regional Police and United Way, told The Pointer in January. “I can assure you that the makeup and dynamics of the team, I don’t think anyone on that roster is afraid to have those tough conversations.”

“I think the makeup of the group is looking for change, I think the community has been looking for change,” he added.

While his words might sound promising, King has done next to nothing in terms of action around the key victories Peel’s Black community has fought for.

Half-a-decade ago, when the issue of police carding that targeted Black youth in Mississauga and Brampton, causing profound alienation, was being confronted, King was not among the community leaders who stood up to former police chief Jennifer Evans and the rest of her force. Crombie deserved credit for taking on the issue.

When the PDSB was finally taken on through a sustained, often heated, campaign, led by Advocacy Peel among others, King was not standing beside them.

Now, sources tell The Pointer it’s demeaning to go through the mayor’s Black surrogate, who isn’t even an elected official, just to communicate their recommendations to her. One asked if white residents have a designated white citizen who screens all requests on behalf of the mayor.

Referring to the dynamic King seems to be a part of, and the failure of the Black Caucus to openly welcome meaningful engagement, Dave Bosveld, a local advocate, recently tweeted, “Are we surprised? We must be pre screened before we may be granted an audience with the Mayor. By our own Black brother.”

Here are some of the actions Advocacy Peel would like to see: The immediate collection of data for all City of Mississauga departments, related agencies and municipal partners to determine current employment demographics, to show if the City is meeting basic requirements for equity and inclusion; the continued tracking of these metrics to determine whether or not hiring, promotions and entry into senior levels of municipal institutions meet human rights and equity standards; other qualitative measurements to track policies and practices that directly impact Black and other visible minority residents in their day-to-day lives.

For a city that is predominantly non white, it is bound to run into trouble if its government continues to shut out racialized groups seeking the same opportunities currently dominated by white employees in lucrative public sector jobs.

In 2017, the City commissioned a diversity and inclusion strategy from the Canadian Centre for Diversity and Inclusion. The strategy, which remains the City’s guiding document, made a number of recommendations City Hall has been slow to act on.

“There has been a lack of progress in implementing any concrete actions in the past four months since the anti-Black racism crisis was declared, there have been many performative actions but not real change, in my opinion,” Melenie Botembe, a Black resident of Ward 2 who has worked part-time for the City, told councillors at an October meeting. “Moreover, I found most of the recommendations from the previous workforce inclusion and diversity strategy from September 2017 — over three years ago — have yet to be implemented.”

The 2017 strategy found, “straight white able-bodied men are more likely to rate the organization as committed to diversity and inclusive than members of equity seeking groups.”

In their responses to Botembe’s presentation, Crombie and Mitcham both repeated past promises. “So this is what we’ve done to date,” Crombie concluded after sharing a haphazard list of all actions to date that could relate to the Black community, including town halls, body worn cameras for Peel Police, the suspension of the Student Resource Officer program and her own anti-Black racism motion in June. Two of those policies, the body worn cameras and the removal of police in schools, had nothing to do with City Hall. The others included no tangible action.

“Change takes time,” Mitcham added, sounding somewhat tone deaf, after four decades of profound demographic shift in the city, which has been largely ignored by those responsible for making sure City Hall reflects the community. “I’m a new CAO, we’ve been faced with COVID over the last more than 6-8 months, but be assured that diversity and inclusion is a priority for (the) City of Mississauga.”

Mitcham and Crombie did not respond to the specifics identified by Botembe in her research on the 2017 diversity strategy or her request that additional funds be allocated to help solve the problem.

Mitcham, who took over the City’s top bureaucratic role last year, has failed to bring forward any type of report detailing a comprehensive, equity-based hiring policy, promotional measures to ensure nepotism and favouritism don’t continue to exclude visible minorites and a recruitment policy that places a priority on diversifying management and the executive ranks.

Last year, Ryerson University released a report that highlighted the glaring lack of Black and visible minority representation at the board level. Black residents made up less than one percent of Canadian corporate boards and in Toronto, where visible minorities represented about 51.5 percent of the population, they made up only 21.7 percent of municipal boards, agencies and commissions.

Corporate Canada, including the government sector, has been hammered by critics who point to white leaders that continue rolling out tired tropes like, change takes time. Meanwhile, ingrained networking structures operate like country clubs, ensuring only those with a connection or immediate reference get included in their exclusive ranks.

Mississauga is inching closer to one of its key objectives.

An externally administered census of all City staff has been completed and is being collated to present to council in the spring. The survey will offer vital insight into the diversity of Mississauga staff at various levels of seniority and will help inform how the City can work to recruit a staff base that reflects the diverse character of Mississauga’s population.

The City says it is making progress on other initiatives, including reworking its human resources department. The release of the survey could act as a watershed to push the City forward, finally.

The council that ultimately makes its decisions and sets the tone for priorities, remains embarrassingly unreflective of Mississauga. One member out of 12 is not white, Dipika Damerla, and she has already secured a nomination to contest the next provincial election, meaning there could be no visible minorities on council in 2022.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

While society continues to diversify and transform, City Hall seems stuck in the past. Words mean nothing without action. More residents are growing tired of being cut off from the economic livelihood that seems to be protected for the privileged.

“A lot of agencies are doing this Black caucus thing,” Iluyomade says. “They’re doing it as a checkbox.”

Email: isaac.callan@thepointer.com

Twitter: @isaaccallan

Tel: 647 561-4879