The Trudeau years have been marked by increased interventionism, rising deficits, an uncertain reform and the worst single tax policy in decades.

by Luc Godbout. Originally published on Policy Options

January 12, 2025

(Version française disponible ici)

How do the fiscal policies of the Trudeau era add up? Whatever political legacy the government leaves behind, there is no doubt these nine years have changed the country’s budget trajectory. For better or worse, this will be the prime minister’s fiscal legacy.

A significant first term

If Justin Trudeau’s legacy were to be remembered for a single fiscal policy, it should be the Canada Child Benefit, introduced at the start of his first mandate. Aimed at helping low- and middle-income families, this benefit replaced the Universal Child Care Benefit and the family tax cut introduced by the previous government, as well as the Canada Child Tax Benefit.

The Canada Child Benefit significantly reduced the poverty rate among households with children between 2015 and 2022. For example, the poverty rate for children living with couples fell from 13.2 per cent to 6.8 per cent, and from 39.2 per cent to 26.9 per cent in single-parent families headed by women.

The first mandate was also marked by reducing the tax rate for the second income tax bracket, from 22 per cent to 20.5 per cent, to offer relief to “the middle class.”

The mandate also saw the Trudeau government introduce carbon pricing in 2019 that is applicable in provinces that do not have an equivalent mechanism. The carbon tax was combined with a rebate for residents of these provinces. By 2024, the rebate for a single person could range from $380 in New Brunswick to $900 in Alberta.

With the support of the provinces, the first mandate also saw improvements to the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and the Quebec Pension Plan (QPP) for future generations. The Old Age Security pension was increased for seniors aged 75 and over.

Of course, one can’t overlook the benefits put in place during the COVID-19 pandemic, from the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) to various business subsidies, including wage and rent subsidies. The government had the ability to act in this context of increased interventionism, and it did.

Increased interventionism financed by deficits

Since taking office, the Trudeau government has never tabled a balanced budget. The Liberal Party won the 2015 election by saying it would “run modest deficits for three years so that we can invest in growth for the middle class and credibly offer a plan to balance the budget in 2019.”

Despite this declaration of intent, at no point was a date set for a return to a balanced budget. Obviously, the measures put in place to combat COVID-19, combined with the rise in interest rates, have contributed to the repeated deficits.

Above all, the Trudeau government chose to be more interventionist.

When the Liberals took power in 2015, federal spending as a proportion of GDP was 14.1 per cent. By 2023-2024, the latest year for which data are official, this had risen to 17.8 per cent. Ottawa’s tax revenue has also increased, but it lagged spending. It rose from 14.0 per cent to 15.7 per cent of GDP over the same period.

The difference between the two, i.e. the deficit, was 2.1 per cent in 2023-2024. Given the size of the Canadian economy, these few percentage points represent tens of billions of dollars added to the debt.

Structural deficit on the rise

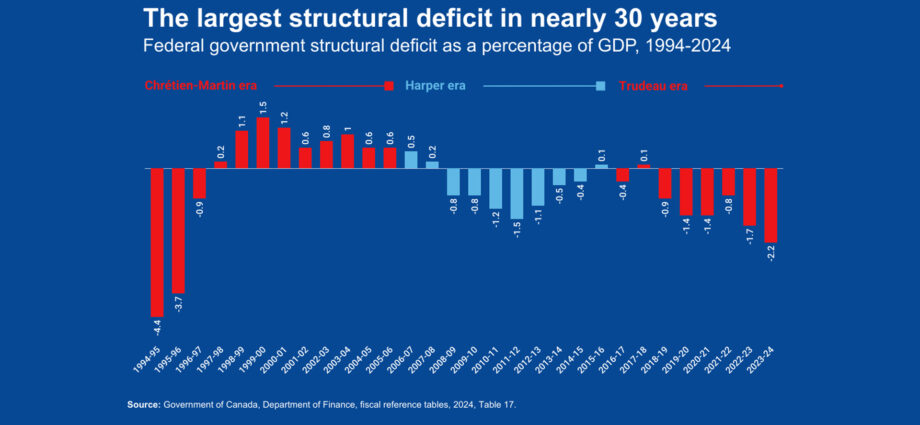

Another way of measuring the impact of a government’s policies is to account for its structural deficit, which can be broadly defined as the negative gap that would remain between revenue and expenditure if real economic activity was equal to the potential level. In other words, without the impact of exceptional events such as a pandemic or an economic crisis on government revenues and spending.

What is the current structural deficit for the federal government?

The most recent figures from the fiscal reference tables show that the federal deficit in 2023-2024 was $62.8 billion once cyclical factors were removed. As a comparison, the structural deficit did not exceed $34 billion during the pandemic years.

Measured as a proportion of the size of the economy, the structural deficit never exceeded one per cent between 2014-2015 and 2018-2019. By 2023-2024, however, it had risen to 2.2 per cent. This represents the federal government’s largest structural deficit since 1995-1996, when Finance Minister Paul Martin sought to eliminate it.

A government has every right to want to increase public service coverage and roll out new programs. However, the federal government should also have identified a source of funding for new initiatives – particularly the permanent ones.

It has done so in part, as can be seen from a non-exhaustive list of changes intended to generate additional revenue: additional taxes on banks and life insurers, under-utilised housing; luxury goods and digital services. The government is also limiting the small-business deduction on the volume of investment income, tightening the alternative minimum tax and increasing the capital gains inclusion rate.

These additional revenues are not enough to cover the increased interventionism. But they have nevertheless had an impact on the tax burden, which has increased.

An increased tax burden due to federal intervention

Figure 2 shows changes in the tax burden in Quebec, i.e. tax revenues collected by all tax administrations as a percentage of GDP, in 2014 and 2023. One can see that the weight of taxation has increased within the Quebec economy due essentially to the increase in federal levies, which have risen from 11.6 per cent of GDP in 2014 to 13.7 per cent in 2023.

Levies for the QPP has also increased to a lesser extent, while the tax burden of the Quebec government has remained unchanged and the burden of local government levies has decreased.

Symbolic budgetary anchors

In her 2023 update, Chrystia Freeland, then finance minister, announced that she would rely on three budget anchors.

The first was to keep the announced deficit for 2023-2024 at or below the budget 2023 forecast of $40.1 billion. The second was to lower the debt-to-GDP ratio in 2024-2025 relative to the fall economic statement (42.7 per cent), and to keep it on a downward trajectory thereafter. The third was to continue the decline in the deficit-to-GDP ratio in 2024-2025, and then to keep it below one per cent of GDP in 2026-2027 and beyond.

One year after from the presentation of these three anchors, one can conclude that they have not been fully respected. First, the deficit for 2023-2024 has been revised upwards to $61.9 billion. The deficit for 2024-2025 has also been raised, from $39.8 billion to $48.3 billion.

The anchor related to the downward trajectory of the deficit-to-GDP ratio has been met after the fact, but only because the 2023-2024 deficit exploded.

Still, the debt-to-GDP ratio projection is declining. Canada also remains the G7 country with the lowest debt burden relative to the size of its economy.

The uncertain fate of capital gains tax reform

In the 2024 budget, Chrystia Freeland sought additional revenue, mainly by reducing the preferential treatment given to capital gains. The impact of this change on corporations, trusts and individuals is in excess of $19 billion over five years. On the face of it, this change alone should have improved the budgetary situation or enabled the federal government to announce the introduction or funding of a significant program.

Even though the measure has been in force since June 25, 2024, the government has still not managed to get it adopted. What happens next is uncertain. When Parliament resumes sitting on March 24, the government may introduce a bill or abandon it altogether. Even a change of government would not necessarily mean the end of the reform, since tax announcements are generally reintroduced by a new government to ensure the predictability of tax laws. In the meantime, taxpayers will be left in the dark until the final outcome.

The GST holiday was a bad idea

The GST holiday appears to be the worst tax policy of recent decades. Political jockeying and populism prevailed over economic logic.

First, it was the wrong policy to achieve the objective of helping low-income households with the cost of living since untaxing certain products generates much greater savings in absolute terms for high-income households. (For example, the richest households spend 3.1 times more on restaurant meals).

Secondly, it is inequitable from province to province. The temporary vacation is 5 per cent in the five GST provinces, but between 13 per cent and 15 per cent in the HST provinces. What’s more, provinces that have repealed their own sales tax to join the HST are left with a revenue shortfall, unless they will be compensated under HST agreements.

Thirdly, the selection of temporarily untaxed products was questionable. For example, while many places in the world are adopting a tax on sweetened beverages to discourage their consumption, a tax vacation has been applied to soft drinks, and even potato chips!

Fourthly, the GST entails significant costs for retailers who, given the temporary nature of the tax break, will have to change their computer systems twice. And that’s not counting the risk of coding errors, leading to an increased risk of assessment for misapplied sales taxes.

The impact of political changes in the country

The upcoming federal election campaign and the current prominence of taxation and its reduction in one form or another in political discourse (“Axe the tax”), it will be interesting to see what the future holds on several federal taxes. In addition, the election campaign will provide an opportunity to see how the various political parties will position themselves with regard to federal carbon pricing, a key measure of the Trudeau era.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

This article first appeared on Policy Options and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.