By Matt Simmons, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, The Narwhal

August 24, 2024

Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs are leading a new wave of pipeline opposition on their lands in northwestern Canada — four years after nation-wide protests shut down railways and roads in a failed bid to halt construction of the Coastal GasLink pipeline in British Columbia.

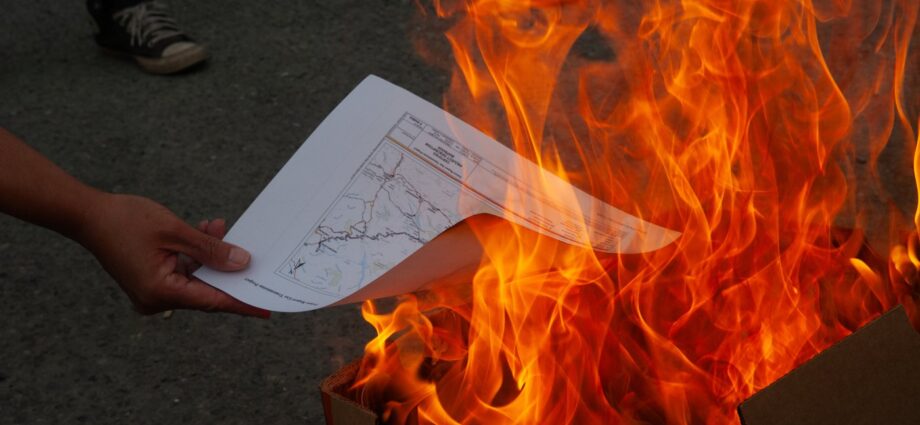

On Thursday, on a remote forest service road in northwest B.C., Gitanyow Simgiget (Hereditary Chiefs) burned a benefits agreement they signed with TC Energy 10 years ago in support of the Prince Rupert Gas Transmission (PRGT) pipeline, saying it will “make our ancestors happy.” The burning ceremony came after the chiefs, supported by dozens of youth from surrounding communities, closed their territories to all traffic related to the new pipeline and set up a blockade.

Construction of the 800-kilometre pipeline — which will ship mainly fracked gas from B.C.’s northeast to liquefied natural gas (LNG) export facilities on B.C.’s coast — is set to begin this weekend. If completed, the new pipeline would cross more than 1,000 waterways, including major salmon-bearing rivers and tributaries.

After closing the Nass Forest Service Road to all pipeline vehicles on Thursday, two chiefs of the Ganeda (Raven/Frog) Clan, Gamlakyeltxw Wil Marsden and Watakhayetsxw Deborah Good, set up a checkpoint where the road meets Highway 37, about 170 kilometres north of Terrace, B.C. The road is the shortest route to transport heavy equipment and supplies for a sprawling work camp being built to support pipeline construction.

“They’re trying to build a 1,000-man camp just down the road at Nass camp, and we’re here to tell them to go around,” Gamlakyeltxw said at the blockade before the agreement was burned. “They’re not welcome. And as far as we’re concerned, this pipeline needs a new environmental assessment.”

The Prince Rupert Gas Transmission pipeline was approved by the B.C. government in 2014, based on environmental studies conducted in the early 2010s. Originally owned by TC Energy, the same company that built the Coastal GasLink pipeline, the project was recently sold to the Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government and Texas-based Western LNG. TC Energy declined to comment on the burning of the agreement or the blockade, instead referring The Narwhal to its website, which notes the company has “completed the sale of PRGT entities to Nisg̱a’a Nation and Western LNG.”

The Nisg̱a’a government, Western LNG and Calgary-based Rockies LNG are partners in a proposed floating LNG facility, Ksi Lisims, set to become the province’s second largest LNG export project. The project, near the Nass River estuary close to the Alaskan border, is currently undergoing an environmental assessment and has not yet been approved by the B.C. government.

As heavy equipment and construction traffic started crossing Gitanyow lands this week, the chiefs announced they no longer support the project, citing climate impacts and the environmental damage caused during construction of the Coastal GasLink pipeline.

“I’m expecting a great-grandson in the next couple of months,” Watakhayetsxw said. “This is his land and I’m going to shout that to whoever can listen. And if we have to close Highway 37 to get that attention, we, the Ganeda, already agreed. [If] the time comes, we’ll shut down Highway 37.”

She described how large flat-bed trailers carrying construction equipment had thundered through their lands the previous night.

“Last night was the last straw, and I will die here if I have to,” she added.

‘Our rivers are drying up’

The Prince Rupert Gas Transmission pipeline will stretch 800 kilometres, from the Treaty 8 territories in B.C.’s northeast that have been heavily impacted by the fracking industry to the mouth of the Nass River on the Pacific coast. It will be more than 100 kilometres longer than the Coastal GasLink pipeline.

The pipeline’s environmental assessment certificate is set to expire on Nov. 25, unless the provincial government deems the project to have “substantially started.” That designation is given by B.C.’s environment minister based on the amount of construction completed, financial costs and other factors. It means the pipeline’s environmental assessment certificate — required for the project to proceed — remains valid instead of expiring.

The Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government, which supports the pipeline, has agreed pipeline construction can begin on Nisg̱a’a lands, which border Gitanyow territory. Construction begins today.

When the pipeline was first proposed in the early 2010s, some Gitxsan and Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs signed contracts with TC Energy and the provincial government, outlining their support for the project and related infrastructure. The contracts detailed how the company would compensate the nations financially in return for permission to build the project through their lands. They also included clauses saying the nations’ leaders should suppress any opposition to the pipeline from community members, including on social media.

But youth say things have changed over the past decade — and that they didn’t have a say in the decision.

At an Aug. 19 youth-led community meeting in the Gitanmaax Hall on Gitxsan lax’yip (territory,) attended by dozens of young people, many spoke in opposition to the pipeline.

Drew Harris, an event organizer who introduced herself as Wet’suwet’en on her mother’s side and Gitxsan on her father’s, said the prospect of another pipeline and increased fossil fuel expansion is frightening in the face of climate change.

B.C. is on the cusp of the biggest fossil fuel expansion in the province’s history. LNG Canada — a liquefaction and export facility in Kitimat which will be supplied by Coastal GasLink — is set to begin shipping compressed gas to overseas markets later this year or early next year.

“The youth and future generations were left out of [the pipeline] conversations, and I’m scared for my future,” Harris said. “Our rivers are drying up. Our fish counts are going down. If we continue to contaminate our waters, pollute our air and deplete our food sources, where does that leave us?”

Patience Muldoe choked back tears as she addressed more than 300 community members seated in the hall.

Muldoe is Gitxsan and grew up on the land. She’s a young member of Wilp Gutginuxw and the Gisk’aast (Fireweed) Clan and a university student and researcher with Gitxsan Watershed Authority. Speaking at the youth-led meeting, she talked about her deep connection with the lax’yip.

“I can’t even imagine a pipeline … ” She trailed off, her voice choked with emotion. “I can’t even imagine a pipeline going through the places where I shot my first moose, where I shot my first grouse.”

Building the pipeline would bring hundreds of workers to the territory, who would cut a wide swath through forests and wetlands rich in biodiversity and crawling with wildlife.

Muldoe told community members how she had just come back from one of those rivers on the lax’yip, where she smudged and swam.

“I wouldn’t even feel safe going on my territory,” she said. “Just let that sink in.”

Honrei Morgan, another organizer and a youth from Gitanyow, said the risks far outweigh any potential benefits the pipeline project could bring.

“I urge everyone here today, mostly the youth, to find whatever it is that will ignite that spark in you to try and protect our lands,” he said. “Because I can tell you right now, no matter how much money may be offered and how much economic growth can come from this pipeline, no sane person can go and be connected to the land and learn about all the great things that it can provide to us and want to destroy all of that and sign it all away to something as crazy as a pipeline.”

Naxginkw Tara Marsden, a Gitanyow member from Wilp Gamlakyeltxw who works with the Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs, said the decision to sign on to the project in 2014 was based on information available at the time. She questioned whether the Gitanyow were given all the data needed to make an informed decision.

“How much information do we have? What is the information that’s available to us? Is it only what the company is telling us? Is it what the government’s telling us? Or is it our own science, our own data?”

Since signing the agreement, the Gitanyow have implemented extensive fish and wildlife programs, gathering vital data about habitat and impacts, including how climate change is affecting their lands and waters. Naxginkw said this makes all the difference.

“We make decisions that affect so many people: people seven generations from now, people downstream, people upstream,” she said. “A billion-dollar cheque is not wealth — that will be gone. Investing in our young people and giving them a chance at a healthy future, that is wealth.”

‘Make our ancestors happy’

“You have to look at these young ones,” Watakhayetsxw said at the blockade Thursday evening. “That’s the reason I’m here. This land isn’t mine, it’s theirs.”

Gamlakyeltxw held up a handful of paper as he stood on the gravel road, his eyes shining. He explained how the agreement between the chiefs and TC Energy had come to be.

“We were told that it was going to go through no matter what, and we said, if it’s going to go through, we’re going to do it right,” he said.

He paused, looking at the agreement in his hands.

“I’m quite proud tonight to have you all here to witness burning this thing.”

Calling the youth to join him, Gamlakyeltxw acknowledged their strength and power.

“You don’t have an identity crisis like we do. You’re proud of who you are and that’s a good thing, and that’s something we didn’t have.”

He knelt and lit the first page. As the youth followed his lead, adding pages to a cardboard box, the flames quickly consumed the document. Gamlakyeltxw grinned as one community member commented: “This is a cultural burn.”

As the flames receded, leaving a pile of ashes on the road, Gamlakyeltxw reflected.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

“We just want to make our ancestors happy. I know they’re very happy we’re here.”