By Rochelle Baker, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, Canada’s National Observer

February 16, 2024

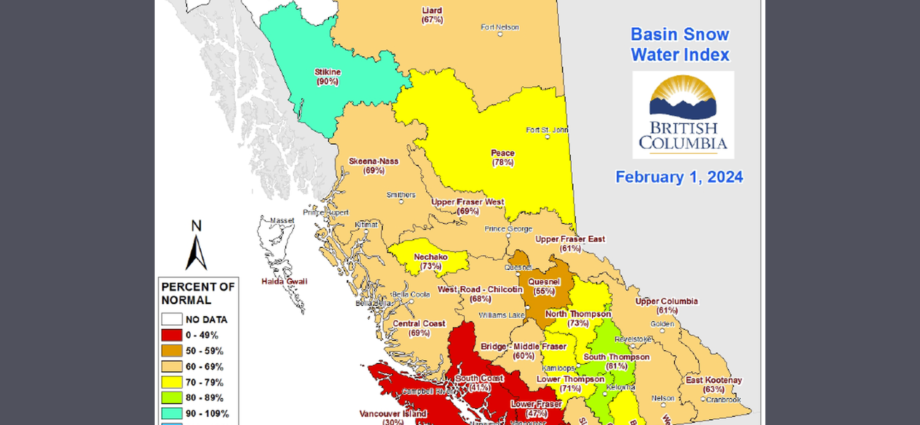

Water security groups in B.C. are rallying to face another summer wracked by drought and wildfire after the province revealed the snowpack is 40 per cent lower than normal. And they are urging the provincial government to do the same.

Extremely low snow levels across most of B.C., ongoing drought in certain areas of the province and unusually warm weather are increasing the risk of widespread drought and wildfire this spring and summer, according to the BC River Forecast Centre’s snow bulletin released Thursday.

Drought hazard levels are pronounced on Vancouver Island, the south coast and the Lower Fraser due to low snowpacks. The risk of water shortages in the Okanagan, Kalamalka and Wood lakes, Nicola Lake and the Nicola River regions are also high as runoff from melting snow is expected to remain low, the centre reported.

Vancouver Island is the hot spot of concern, with a snowpack that’s 70 per cent below normal. The south coast is 60 per cent lower, the Lower Fraser is 53 per cent lower and Quesnel is 45 per cent.

Snowpacks typically act as natural reservoirs, feeding water to communities, farmers, wildlife and watersheds as they melt in warmer, drier summer months.

However, this year’s snowpack situation is worse than last year when snow levels were 20 per cent lower than normal — only to be followed by a summer provincewide water shortages and a fire season that razed 2.84 million hectares of land and forced the evacuation of tens of thousands of residents.

It’s no surprise climate change has increased the frequency of drought, flood and fires, said Oliver Brandes, a lead with the POLIS Water Sustainability Project at the University of Victoria.

But the speed and severity of these climate impacts demand a paradigm shift on dealing with them, Brandes stressed, noting water shortages are no longer temporary, unexpected events that communities simply must ride out.

“Really, we’re facing a new reality. Think about it, here we are talking about drought in February,” he said.

“It’s good because at least we’re thinking about it beforehand, but it’s bad because it’s a terrible sign of a really problematic situation.”

The province must show leadership to plan ahead to mitigate drought in conjunction with communities, First Nations, local governments and regional water users before the peak of a crisis, he said.

Suddenly turning off the tap for farmers, industry and other commercial users relying on groundwater with no collective advance planning or conservation efforts when water shortages reach crisis levels in July or August, which happened last summer, isn’t an effective way to manage drought, he added.

“The worst thing to do is be two to three weeks into a drought and then decide who’s going to have their water cut off,” Brandes said.

“People need to know in advance so they can organize themselves and it can be fair … and they don’t feel like they are being unfairly targeted.”

The province licenses and regulates ground and surface water typically relied on by rural commercial users who aren’t tapped into municipal systems.

Last summer, industrial water users and farmers growing water-intensive forage crops on central Vancouver Island faced provincial water restrictions in the Tsolum and Koksilah and Cowichan river systems, as did many water licence holders in the Thompson Okanagan region.

The province also needs to get a handle on how much ground or surface water is being used across the province, by whom, and for what, he added.

“You can’t manage what you don’t measure,” Brandes said.

“When you’re coming out of [a] winter where drought never really left and [have] a tough season ahead, one can certainly question whether water bottlers, golf courses and splash parks should be priorities.”

Water, Land and Resource Stewardship Minister Nathan Cullen said the province is aware of the increasing likelihood of severe drought conditions again this year.

“Unless conditions become wetter in the months ahead, the potential for drought conditions is very real and our government is already taking steps to help people prepare,” Cullen said in an emailed statement.

“We are determined to take action, and have already boosted community emergency response grants, agriculture water infrastructure grant, fisheries protection and [created] a $100-million watershed security fund.”

However, the minister’s office did not clarify if the province intends to begin requiring large-scale consumers to meter or report their water use, or if it is considering raising rates for high volume industrial water users to encourage conservation and to reinvest into provincial water security.

Farmers and ranchers face some of the toughest challenges from drought, Cullen said, adding the province is working now with farmers to prepare for the summer.

On Wednesday, the Ministry of Agriculture and Food announced it plans to hold workshops in more than 30 communities to help farmers weather potential water shortages and provide information about available financial support.

The province recently crafted new regulations that allow fines for people who violate the Water Sustainability Act of up to $100,000 for a general offence and up to $500,000 for serious penalties.

“As we experience more severe drought seasons due to climate change, there’s a role for all orders of government, businesses, organizations, First Nations and people to work together and find solutions,” Cullen said.

The province is developing a watershed security strategyslated for release sometime this spring, which includes a goal to set up regional watershed tables so First Nations, local governments, communities and water users can shape local solutions.

One regional roundtable is up and running and already at work to try to buffer impacts for all users in the water-strapped Nicola watershed in B.C.’s Interior, said Brian Holmes, councillor with the Upper Nicola Band.

In total, the Five Nicola First Nations Governments — including the Coldwater, Lower Nicola, Nooaitch and Shacken Indian Bands — have established the Nicola Watershed Governance Partnership (NWGP) with the province, Holmes said.

Drought compounded by serious fires and floods are ongoing issues in the region, said Holmes, the NWGP’s co-chair.

“The difference is now with this partnership, we have a collective voice with government and First Nations,” Holmes said.

“We’re looking at pulling in Indigenous knowledge and laws into the decision-making, which was missing before.”

Taking a holistic view of water use in the region that incorporates environmental concerns and First Nations uses as well as the needs of other water users is critical to caretaking the resource, he said.

But establishing partnerships, trust and co-operation with all water users before hard decisions have to be made is critical, he said.

“It’s really important to kind of share information and thoughts about what management needs to be changed or done in terms of making this water system a little bit more sufficient for agriculture, industry and Indigenous cultural and ceremonial needs,” he said.

The watershed roundtable is exploring solutions such as using surrounding lakes as natural water reservoirs and is sitting down now with ranchers to find conservation solutions, discuss irrigation shutoffs, how to boost fish survival in low rivers, and more efficient watering systems.

“We’ve done it through the winter because when it comes into late summer, we’re getting into that reactive stage where drought is happening,” Holmes said.

As long as there’s communication about why and what water measures are needed most water users want to work to find solutions to water shortages, he said.

“Each rancher or private landowner around here has some ability to support conservation of water,” Holmes said.

“So, yeah, it’s been noticeable, less conflict, and more willingness to work collectively to address the issues.”

Rochelle Baker / Local Journalism Initiative / Canada’s National Observer

Subscribe to our newsletter.