A record number of Canadians believe that their health care systems need a complete overhaul.

by Olivier Jacques, Marion Perrot. Originally published on Policy Options

May 3, 2023

(Version française disponible ici)

The COVID-19 pandemic has hit Canada’s already strained health care systems, causing significant human suffering and loss, as well as a severe economic impact. Have the health systems themselves been affected? Canadians believe so, and see the Canadian health care system as being in trouble.

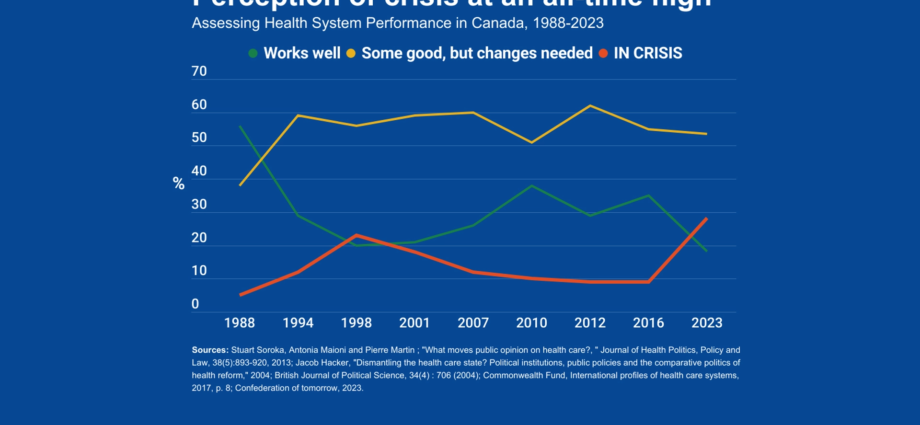

Only 18 per cent of Canadians believe their health care system is “working well,” the lowest proportion in 35 years. Some 54 per cent believe that changes “are needed.” And 28 per cent think the system is in “crisis,” a record high.

This is according to data from the 2023 Confederation of Tomorrow Survey, conducted by Environics Institute in partnership with the Canada West Foundation, the Centre for Policy Analysis – Constitution Federalism, the IRPP Centre of Excellence on the Canadian Federation, the Brian Mulroney Institute of Government and the First Nations Financial Management Board.

The data show an increase in the perception that Canada’s health care system is in trouble.

Figure 1 compiles all available surveys asking the same question since 1988 about the functioning of the health care system. It was possible to answer that 1) the system is working well and only small changes are needed, 2) there are good things about the health care system but fundamental changes are needed, or 3) our health care system is so bad that we should rethink it entirely. This last option suggests that respondents think the system is in crisis.

In 2023, three times as many Canadians believe their health care system is in crisis than in the three surveys of the 2010s (28 per cent in 2023, compared to 10 per cent or less from 2010-2016). This is the highest percentage recorded, surpassing 23 per cent in the late 1990s.Yet, this period was defined as a point of greatest stress in the health system following federal cuts to health transfers and subsequent provincial austerity in the networks.

Our preliminary analyses of the data suggest that respondents on the left and those who are more likely to use the health care system are more likely to think it is in crisis. Moreover, this perception that the system needs a complete overhaul varies considerably across provinces, as shown in Figure 2. Respondents in wealthier and younger provinces are less likely to describe the health care system as being in crisis. In contrast, those in less affluent and aging provinces are more pessimistic. In both cases, the correlation is very strong. This explains why people in the Atlantic provinces, who are feeling the full impact of an aging population and a less dynamic economy, are the most likely to believe that the entire system needs to be rethought.

Does higher health spending reduce the perception of crisis? The data suggest that it does not, as shown in Figure 3. There is only a weak correlation between spending levels and perceptions of crisis, or not. In fact, the three provinces whose residents most perceive their system to be in crisis – New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Nova Scotia – maintain very different levels of per capita health spending. Respondents in Alberta, British Columbia and Ontario are more likely to think their system is working well, while these provinces maintain somewhat lower spending, but have younger and wealthier populations.

Blaming Ottawa or the provinces?

We also asked respondents whether the problems of their health care system were caused by inadequate funding or ineffective management. This can certainly be linked to Canadian federalism, since management is necessarily provincial, while the provinces tend to blame the federal government for inadequate funding.

Thus, half of the respondents were asked to take a stand and choose whether the main cause of the health care system crisis was due to lack of federal funding or to provincial management. The data collected was then compared with previous surveys conducted each year between 2002 and 2012.

As shown in Figure 4, the percentage of respondents indicating that the problems are primarily due to inadequate funding almost doubled between 2012 and 2023, rising from 26 per cent to 40 per cent and reaching the highest 2002 level. Thus, while the perception of a health care system in crisis is at its highest level, more citizens than before believe that inadequate funding is the primary cause of the problem. Ineffective management has gone the other way, sliding from 62 per cent to 42 per cent between 2012 and 2023.

It should be noted that for surveys conducted between 2002 and 2021, respondents could also choose both options (funding and management), an answer chosen, however, by only 1-12 per cent of respondents. Attributing funding problems to the federal government and management problems to the provinces (see 2023 – Wording experiment in figure) rather than simply management and funding does not appear to change responses at the aggregate level, although our preliminary analyses suggest that some individuals are more influenced by the attribution of the problems to a particular level of government.

When attention is paid to the distribution of responses by respondents’ province for the 2023 survey, most hover around 50-50. Quebec is the exception: 60 per cent of Quebec respondents think management is the problem, compared to 40 per cent who blame funding. Residents of Alberta and New Brunswick are also more likely to blame poor management (56 per cent and 57 per cent respectively). This contrasts with Saskatchewan, where 56 per cent of respondents see funding as the main cause of problems.

Respondents who think the system is in crisis are more likely to blame management. This is the case for 59 per cent of respondents who see the system as being in crisis, compared to 41 per cent who point to funding, as shown in Figure 5. Respondents who believe the system is not in crisis have no significant preference: the distribution between blaming funding and management is almost equal (49 and 51 percent).

Figure 5

Finally, our preliminary analyses and Figure 6 suggest that individuals who feel that the system is in crisis and who blame (provincial) management tend to want the federal government to impose conditions on health transfers. Thus, perceptions of the state of the health care system are inevitably linked to major issues in Canadian federalism.

Figure 6

Subscribe to our newsletter.

This article first appeared on Policy Options and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.