By Frey Blake-Pijogge, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, The Independent

September 20, 2025

Inuit in Labrador have been bearing the brunt of climate change for years now, forcing those in Nunatsiavut to adapt to conditions that are changing their way of life and impacting their health. In turn, Nunatsiavut Government, the self-governing body for Labrador Inuit, is taking matters into its own hands with a new strategy detailing how it will help mitigate climate change in Labrador and assist Inuit in adapting to the changing environment and conditions impacting their way of life.

Labrador is experiencing the thaw of permafrost, rapid sea ice changes, precipitation changes, sea level changes, and wildlife and vegetation changes due to climate change at a rate higher than in the south.

According to Climate Data, a collaboration between the federal government and various research bodies, the annual average temperature in Nain, Nunatsiavut from 1971-2000 was -3.4°C; Nain is now projected to see an annual average temperature of -0.4°C between 2021-2050. In the southern part of the province, St. John’s had an annual average temperature of 5.1°C between 1971-2000, and now has a projected average temperature of 7.1°C between 2021-2050.

Since 2020, the federal government says it has announced more than $2 billion in funding for climate action by Indigenous Peoples. This funding would support improving food security in the north, including in Inuit Nunangat, the homeland of Inuit in Canada, with $163.4 million over three years. In April, Indigenous Services Canada announced $95,000 in funding for food banks and community freezers in all five Nunatsiavut communities to help improve food security amid barriers brought by climate change to access country food.

But Nunatsiavut Government’s new climate strategy has been created to ensure Inuit values, priorities, and knowledge systems are at the core of climate actions for communities in Nunatsiavut.

‘Adapt Nunatsiavut’: an Inuit approach

In March, Nunatsiavut Government released Sungiutisannik Nunatsiavummi (Adapt Nunatsiavut): An Inuit Approach to Climate Change Mitigation & Adaptation in Nunatsiavut, its first climate plan. The strategy addresses climate change impacts in Nunatsiavut communities, community engagement, plans for adaptation and mitigation, timelines for implementation of strategies, all with Inuit-led governance at its core.

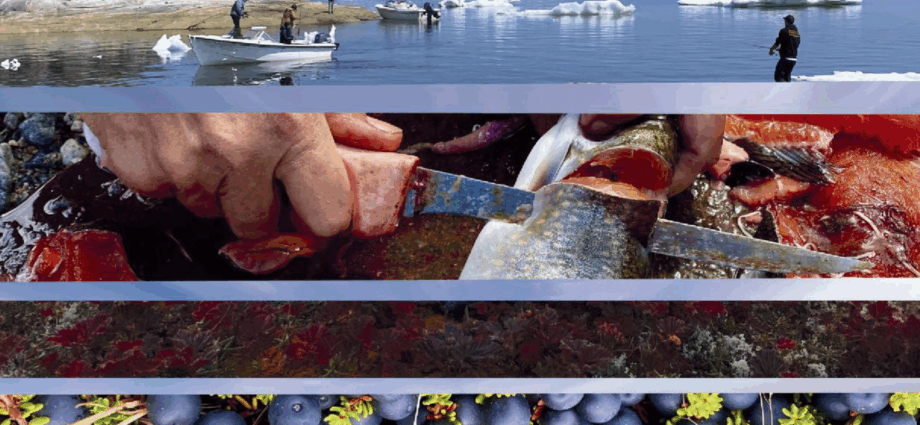

Nunatsiavut is the area comprised in the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement in northern Labrador and includes the communities of Nain, Hopedale, Makkovik, Postville, and Rigolet, home to more than 2,000 Inuit. The land claim area spans 15,800 square kilometres, with its communities scattered along the coast of the Labrador Sea and its residents heavily dependent on fishing, hunting and other traditional ways of life.

Former Nunatsiavut Government Climate Change Manager Chaim Andersen says Labrador’s warming climate is contributing to thawing permafrost, changes in precipitation, sea level changes and sea ice conditions. She says it’s also impacting wildlife and vegetation — all of which, she says, is negatively impacting Inuit culture and ways of life. “There are changes to our lives, specifically as Inuit, and as people who hunt and fish and are going out on the land consistently, so we’ve seen a lot of changes to our way of life.”

The Nunatsiavut climate strategy outlines implementation plans, monitoring and evaluation, funding, governance, engagement and communication, and actions Nunatsiavut Government began taking on mitigation and adaptation, with no end to the timeline. The strategy outlines short-, medium- and long-term plans.

Andersen, who has taken on a new position with Nunatsiavut Government since the time of this interview, highlights the climate change impacts on Inuit health and well-being in the strategy, of which connection to the land and maintenance of a traditional lifestyle is vital to Inuit health and well-being. “Health and well-being is often improved when we’re able to practice our culture, when we’re able to go to the cabin locations, and we’re able to spend time with each other on the land practicing our traditions,” she explains. “So when there are significant changes in the environment that prevent us from being able to do that, then naturally health and well-being is infringed upon by climate change.”

Andersen says the changes are contributing to increased stress, anxiety, and fear of the risks to Inuit safety, including the feeling of isolation in Nunatsiavut communities. She says Nunatsiavut’s approach to climate action involves creating space through various workshops and community engagements so that community members can share their concerns about climate change.

Priority areas in Sungiutisannik Nunatsiavummi include the environment, infrastructure and transportation, economic development, food security, health and well-being, energy, culture, and education — all of which have been informed by traditional Inuit knowledge from community members.

Andersen explains Nunatsiavut communities often experience energy poverty, which, alongside a rising cost of living, has left “many people” struggling to heat their homes. Though energy poverty is just one of the strategy’s priority areas, each area has its own proposed plan to resolve or help Nunatsiavut communities adapt to the impacts of climate change.

Climate justice, with Inuit self-determination and decolonization at its core, is highlighted in the strategy. “Making sure that Inuit leadership is guiding every single step of the strategy and also advocating for Inuit led-governance,” Andersen explains. This also includes addressing colonial frameworks to be historically limiting to Inuit, which she says is different compared to traditional Inuit governance before colonization.

“Inuit and northern communities contribute minimally to global greenhouse gas (emissions) while we are faced with huge impacts of climate change. The Arctic is warming up more than twice, and potentially up to four times the global average, and this is driving the impacts of climate change in communities,” Andersen says.

The strategy’s section on climate justice addresses the federal government’s Bill C-226, also known as the National Strategy Respecting Environmental Racism and Environmental Justice Act, passed in June 2024. The legislation addresses environmental racism perpetrated on racialized communities in Canada, including Indigenous communities, and examines the links between race and socioeconomic status and the exposure to environmental risks that are disproportionate than to non-racialized communities. The climate change strategy says Bill C-226 “will only be meaningful if it directly addresses the disproportionate climate impacts on Northern and Inuit communities. Climate adaptation in Inuit Nunangat must be a core pillar of Canada’s commitment to environmental justice, reconciliation, and climate action.”

Nunatsiavut is one of four regions in Inuit Nunangat, alongside Nunavik in northern Quebec, Nunavut, and Inuvialuit Settlement Region in northern Northwest Territories.

Andersen explains the Labrador Sea acts as a carbon sink, absorbing more carbon dioxide than what Nunatsiavut emits by 800 times over. “So this is a really good example of injustice in terms of the impacts that our communities are feeling, as opposed to the amount of funding and support and leadership that we have on the global scale,” she says.

Nunatsiavut Government was approved for the formation of a trilateral climate table alongside the federal and provincial governments to serve as an intergovernmental forum for climate change issues that transcend governmental boundaries. Funded by the federal government, Andersen says the strategy has laid out mechanisms for the Inuit government to exercise self-determination.

The Nunatsiavut climate strategy aligns with broader climate goals outlined in Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami’s National Inuit Climate Change Strategy, Canada’s National Adaptation Strategy, and Newfoundland and Labrador’s Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Action Plans. It also updates its communities on implementation of the strategies while coordinating further community engagement to listen to Inuit voices and concerns on climate change.

Nunatsiavut Government also plans to create a website to inform the public about climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies implemented, and to have a platform Inuit can use to voice their concerns online.

Turning climate dread “into a strengths-based perspective that focuses on leadership, that focuses on resilience and focuses on what strengths we have in our communities to take actions, as opposed to focusing on the issues,” is important, Andersens says. And “allowing space for those issues to exist while also empowering people to feel that there is a pathway forward, even if it is not apparent.”

In Part 1 of this 2-part feature, The Independent spoke with Elders, hunters and advocates about the ways climate change is impacting the health, food security and culture of Inuit in Nunatsiavut. Read that article here.

Read part one here

Subscribe to our newsletter.