September 11, 2024

Hurricanes and typhoons are becoming stronger as sea temperatures rise, according to meteorology organisations and climate researchers around the world

Super Typhoon Yagi made landfall in Vietnam last week, destroying buildings, sinking boats, and triggering landslides across the country, resulting in 14 deaths. Meteorological authorities in Vietnam labelled Yagi as “one of the most powerful typhoons in the region” over the past 10 years.

This comes after another powerful typhoon ripped through Japan at the end of August, leaving eight people dead. On the other side of the world, U.S. meteorological forecasterswarned that this year’s hurricane season, between June and November, could be “extraordinary.”

The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) stated that its data has shown that it is “likely” these storms are getting stronger over time. A higher proportion of hurricanes and typhoons are reaching “category three” status or above than in previous decades.

How tropical cyclones are formed

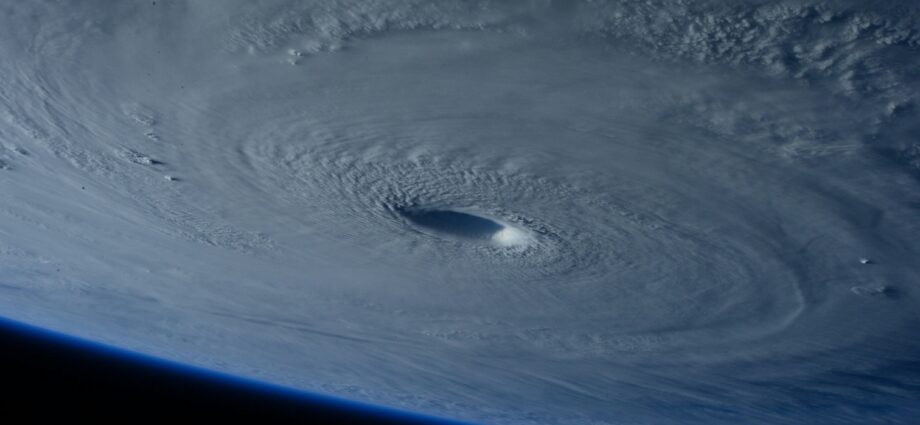

Hurricanes and typhoons, also known as tropical cyclones, are stronger-than-usual storms that develop in warm ocean waters such as in the Caribbean and in Southeast Asia. Each year,between 80 to 90 notable tropical cyclones form around the world.

As warm, humid air rises from the surface of the ocean, the storm cloud begins to form. Strong winds in tropical regions then cause the storm clouds to spin at higher and higher speeds. Generally, the surface of the sea must be at least 27 degrees Celsius (80 degrees Fahrenheit) for a cyclone to develop.

These high wind speeds, heavy rainfall, and short-term rises in sea levels — or storm surges — create potentially lethal conditions in places where these tropical cyclones make landfall.

These storms are categorised by their peak sustained wind speed. In the U.S., category one cyclones’ wind speeds reach between 119 and 153 km/h (74-95 mph) and category five cyclones concern any storm above 252 km/h (157 mph).

Typhoons, hurricanes and climate change

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), cyclone intensity has increased notably over the past three decades, despite the total number of cyclones per year remaining relatively constant since 1878.

Following fluctuating cyclone intensity for most of the latter half of the 20th century, a significant increase has been noticed since 1995. This variation and then increase are associated with changing ocean temperatures over the same time period that come from climate change.

As ocean temperatures rise, so do the chances a milder storm can pick up energy and speed in warmer waters. This year, an unprecedented four to seven “major” Atlantic hurricanes were forecasted, in part due to record-high Atlantic sea surface temperatures.

Aside from the wind strengths of these cyclones, warmer atmospheres — which hold more moisture — can lead to heavier rainfall. According to a study published in IOPscience, extreme rainfall during Hurricane Harvey in 2017 was made three times more likely due to climate change.

Moreover, as sea levels rise due to melting glaciers and ice sheets, the risk of storm surges increases as well. The resulting damage caused by storm surge floods can be devastating. It is estimated that during Hurricane Katrina in 2005 — which caused over $160 billion in damages — peak flood heights were at least 15% higher and up to 60% higher than they would have been in 1900 climate conditions.

Research at World Weather Attribution (WWA) found that Typhoon Gaemi, which left more than 100 dead in the Philippines, Taiwan and China, was made significantly worse by fossil fuel-driven climate change.

Ben Clarke, who took part in this research and works at Imperial College’s Grantham Institute for Climate Change and the Environment in London, said bluntly that “fossil fuel-driven warming is ushering in a new era of bigger, deadlier typhoons.”

Tropical cyclones in the years to come

The U.S. Global Change Research Program and the IPCC both estimate that tropical cyclones will continue to intensify in strength over the 21st century, causing more devastation than previously seen.

The IPCC warns that it is “very likely” tropical cyclones will continue to have higher rates of rainfall and reach higher wind speeds than those of the past century. The rises in global temperatures are directly proportional to the rises in extreme storm conditions.

The percentage of tropical cyclones that reach category four and five are expected to increase by around 10% if global temperature rises are limited to 1.5 degrees Celsius — the optimistic goal of the Paris Agreement in 2015 — according to the IPCC. Should temperature rises reach 2 degrees Celsius, this increase could reach 13%.

In the event global temperatures rise up to 4 degrees hotter than pre-industrial levels, 20% more hurricanes are estimated to reach the highest categories of strength.

With increased intensity comes increased damages and casualties. Between 2017 and 2023, 137 billion-dollar natural disasters have cost the U.S. over $1 trillion in damages, mostly caused by category four or five hurricanes, including Hurricanes Harvey, Ian, Ida, Irma, Maria, Michael and Laura.

The United States’ proximity to the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico makes it especially vulnerable to these cyclones, but they are not the only ones. In the Pacific, Typhoon Doksuri in 2023 caused over $28 billion in damages, mostly in China. Japan’s Typhoon Hagibis resulted in $18 billion worth of damages in 2019. Hong Kong experienced $593 million in direct economic losses from 2018’s Super Typhoon Mangkhut.

This is only the economic impact; these storms also resulted in thousands of deaths and tens of thousands of injuries and displaced people.

It is becoming widely accepted that global warming is leading to stronger and more devastating storms, particularly in the Caribbean and in Southeast Asia, with some experts even arguing to add a hypothetical new category, category six, to the scale.

With these intensified storms, there will be more human loss and displacement and more economic damages than in years before. While these cyclones are a natural occurrence, their increased devastation is yet another side-effect of man-made climate change.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

This article was originally published on IMPAKTER. Read the original article.