Access to information is a shambles. Without a free flow of government documents, assessing how past policy prescriptions fared is impossible.

by Timothy Andrews Sayle, Susan Colbourn. Originally published on Policy Options

November 25, 2021

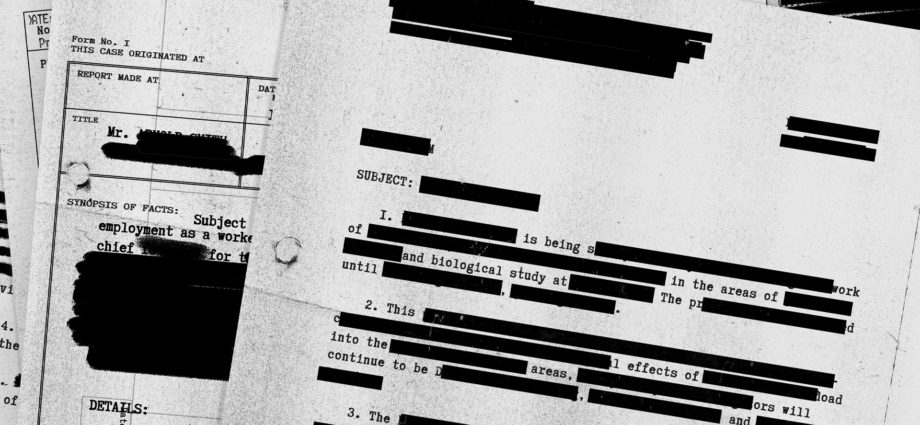

Prime Minister John Diefenbaker rose in the House of Commons to make an important announcement on February 20, 1959. He was about to cancel the Avro Arrow. “Canadians will be glad to know . . .” the prime minister began. But what Diefenbaker thought Canadians would wish to know had to remain classified – or so the Privy Council Office (PCO) maintains, deeming the 62-year-old public statement likely to be injurious to Canadian international affairs or defence.

In response to a recent request for government records under the Access to Information Act, the PCO responded with a redacted version of the Hansard. After the curious sanitization got some attention on Twitter, the PCO responded with a full – and unredacted – copy of the prime minister’s speech. Of course, anyone interested in the speech can already read it in full with a few clicks.

But the redaction of records explicitly intended for public consumption is not the problem. Rather, it is symptomatic of a much larger problem: the Access to Information Act is a shambles.

A broken system

In its official rhetoric, the Government of Canada touts openness, transparency and accountability as the guiding principles of government. In practice, the situation is much more opaque. Even decades-old materials remain restricted, tucked away in various departments in Ottawa, including Library and Archives Canada.

This secrecy about historical events is damaging to Canadians. History can be a critical asset in the making of policy, offering a laboratory of sorts to see how prior policy prescriptions fared. To do so, it is imperative that we know the ins and outs of these earlier efforts to figure out why they succeeded or failed, as well as the short- and long-term consequences of those choices. Without documents, that task is almost impossible.

In the case of the Avro Arrow request, the PCO still retains about 100 pages of historical records from the file. There is no reason this information from the 1950s should be kept secret in the 2020s. Most of the documents are already available at Library and Archives Canada, in the files of the Department of National Defence. The PCO either doesn’t know or doesn’t care that the secrets it is guarding are not secrets to be protected at all. They aren’t even secrets.

The government is keeping vast amounts of information secret that other departments of the same government have made readily available to interested Canadians. In one department, a document might be open and freely released to a requester; in another, the same information is withheld on the basis that its release could do great damage to Canadian interests.

Canada desperately needs to revisit its policies and legislation regarding access to historical records. The Access to Information Act is an inappropriate tool for managing historical records because it ignores the possibility that a document might become a piece of history. Under the Act, there is no difference between documents produced yesterday and those produced by Pierre Trudeau’s or Mackenzie King’s government. Historians file the same requests for classified archival materials as journalists do to delve into the most pressing issues of today.

A 30-year rule – in which the bulk of records would be released after three decades, with exceptions reserved for only the most sensitive of government secrets – would make it possible to write much more of Canada’s recent history. At this rate, we’d even settle for a 50-year rule, just to see documents released to the public.

We need a comprehensive framework for declassification – something every other NATO country has – and a national declassification centre. Neither will happen overnight. But there are cheap, easy solutions that could help reduce the enormous backlog of historical records that are still unavailable. These measures could save the federal government time, money and embarrassment.

Keep track of what is open

Sanitizing a prime minister’s speech in the House of Commons might be egregious, but the practice of restricting information already readily available in the public domain is a regular occurrence. Release packages often include redacted versions of historical records that have already been published as part of the government’s own series, Documents on Canadian External Relations. Even more frequent is the redaction of documents already released by another department as part of a previous request under the Access to Information Act.

A simple, but radical shift could dramatically improve this situation. What if the government kept track of what information has already been released to the public?

Take, for example, the original request to the Privy Council Office regarding the Diefenbaker redactions. Among the pages deemed potentially injurious by the PCO is a largely redacted document: this cover letter from the Department of National Defence to the Privy Council Office. What was released as part of this Access to Information request included only the most basic details: the document’s date, a file number and the author’s name. That file, “CSC 1889-1,” is a Department of National Defence file that is held at Library and Archives Canada. The cover letter is open at Canada Declassified, and so is the attached “draft of proposed agreement with the United States on the acquisition of nuclear warheads for Canadian Forces.”

The government had already conducted a line-by-line review of this document and concluded it could be released. In 2021, a different arm of government repeated that same work – and came to the opposite conclusion. As a result, a researcher will likely complain to the Office of the Information Commissioner, which means investigators, meetings and even more time spent on the matter, all to discuss a document that had already been made available to another requester.

Requesters frequently run their release packages through programs that make the PDF material machine-readable. As a by-product of this cheap and easy process, it is easy to identify when previously released information is later sanitized. Imagine if the government harnessed this technology to shed the burden of trying to keep secret information that is already public.

Leverage requesters’ knowledge

Often when a requester files for the release of materials under the Access to Information Act, that person already knows a great deal about the subject and what is available in the public record. What if, as part of the request process, the requester was encouraged to provide details about information that is already released?

Some departments do take requesters’ knowledge into consideration. They can provide examples of material that is already available, whether through releases from the federal government, from other governments and their national archives, or in published memoirs. This can greatly reduce the resources expended on requests, a boon to researchers and government departments alike.

Other departments have yet to make the most of requesters’ expertise. Take, for example, a recent request that produced a heavily redacted copy of a 2002 memorandum to Prime Minister Jean Chrétien regarding the possible invasion of Iraq. That same memo is already published in full in Chrétien’s own memoirs. E-mails regarding the discrepancy go ignored.

We know of many other efforts by requesters to advise departments, during or after the processing of a request, that similar information is already available in Canada or other national archives around the world. For the most part, however, it seems that the presence of information in the public record (even if put there by the federal government) has no effect on new access to information reviews for the same information.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Historians filing access requests for documents from the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s are not trying to “expose” or “embarrass” the government. We are seeking to learn from the past in the hopes of informing Canada’s future. But the message interested Canadians get from their government is that this history should stay closed ─ that we cannot or need not know the truth, even things that a previous prime minister thought we would be glad to know and shared openly in the House of Commons.

This article first appeared on Policy Options and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.