By Sierra D’Souza Butts, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, The World-Spectator

February 14, 2022

Transparency International released its annual Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) for 2021 in which it reports that Canada dropped three points to 74, its lowest ranking ever, but is the 13th least corrupt country of the 180 countries tracked by the index.

The report also finds 131 countries across the world have made no significant progress against corruption in the last decade.

The CPI is based on a scale where zero is highly corrupt and 100 is least corrupt. Out of the 180 countries, Denmark Finland and New Zealand were at the top of the index with a score of 88. Canada ranks 13th out of 180.

James Cohen, executive director of Transparency International, explained the difference between a country being placed at the top of the list, compared to a country being placed at bottom for being the most corrupt.

“There’s a general good performance of rule of law, where transparency in how government’s day-to-day functions that do not require citizens to pay a bribe. There’s transparency of contracts and business,” Cohen said.

“Where as the bottom ranked countries, you can almost say bribery is the means of everyday living for citizens. Where as here (in Canada), we’re used to paying taxes, having accountability attached to them, published budgets by different levels of government, and different bodies having oversight over those budgets that can publish audits and reports on whether if they were properly spent or not. None of those functions would exist in the lowest performing countries. Citizens and businesses are just kind of reliant on working day-to-day and who they’ll have to pay day-to-day.”

Canada is still near the top of the list with a score of 74, but that is its lowest score ever. Canada ranks the same as countries like Iceland, Ireland, Estonia and Austria. Countries such as South Sudan, Syria and Somalia, remain at the bottom of the index.

However, Cohen emphasizes that despite a country like Canada being placed near the top of the list, does not mean they are not interacting with a lower ranking country who was placed at the bottom of the index.

“It’s important to emphasize that the top ranking countries have their own transparency accountability and corruption problems. Canada might be out of the top 10 (it’s 13th this year) but we still have issues,” Cohen said.

“It’s been noted in the map of the Corruption Perception Index, that corruption doesn’t often stay within national borders. The countries that are most highly ranked are being called out for our role, in facilitating global corruption, global financial floats. It’s important to take that interconnectedness of global corruption in to mind as well.”

He said the global level of corruption is important to focus on because a country that is ranked for being the least corrupt, may still be conducting business with a country who is ranked for high corruption.

“Often large scale corruption rarely stays within borders. Let’s say a Canadian company works in a country that ranks really low on the CPI, that Canadian company let’s say pays a bribe to an official.

“There’s a good chance that money won’t stay in the country where they paid the bribe. It will go into a bank account in a secrecy jurisdiction where there’s a team of enablers, lawyers, accountants, bankers, financiers who will guide that official on how to max that money and layer it, move it through a number of other jurisdictions, and then it may very well wind up back in Canada anonymously buying property here, or integrating with criminal networks here.”

“The money moves around the world through different actors and through different countries, a lot of those are top performing CPI countries, so that’s how the global system works,” said Cohen.

The purpose of the CPI is not to rank the number of corruption cases that occurred in a nation, but rather to showcase how protective systems n a nation are, against corruption.

What data doesn’t the CPI rank?

“One thing that the CPI does not rank is the number of corruption cases that have been found out or convicted, because you just don’t know how many there are by its very nature of corruption. So it’s more about what systems are in place to protect against corruption,” said Cohen.

The CPI also does not cover citizens’ direct perceptions or experience of corruption, tax fraud, illicit financial flows, enablers of corruption (lawyers, accountants, financial advisors, etc.), money laundering, private sector corruption and informal economies and markets.

The data sources used to compile the CPI of public sector corruption includes: bribery, diversion of public funds, officials using their public office for private gain without consequences, ability of governments to contain corruption in the public sector, excessive red tape in the public sector which may increase opportunities for corruption, nepotistic appointments in the civil service, laws ensuring that public officials must disclose their finances and potential conflicts of interest, legal protection for people who report cases of bribery and corruption, state capture by narrow vested interests, and access to information on public affairs/government activities.

What’s the purpose of CPI?

The annual Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) has been published since 2011.

Cohen said the purpose of the index is to make countries aware of where they stand on a corruption level amongst the general public.

“The Corruption Perceptions Index was developed in the 1990s by Transparency International as a way to bring global attention to the plaque of corruption, and to get attention on the subject,” said Cohen.

“It’s been working that every year countries take notice, and each chapter around the world tries to dissect further, and look into the explanations to why a country has gone up or down.”

“But, primarily overall, to see what the state of what corruption is around the world and bring attention to it.”

He said the data that is used to collect a country’s corruption rate, comes from a number of different sources that provide perceptions among business people and country experts, of the level of corruption in the public sector.

“There are 13 sources that our office in Berlin, who runs the report, use. For a country to be on the CPI there needs to have been at least three sources that gather data, so for Canada this year there were eight sources that gather information.”

He said the purpose of the index is to hold countries accountable for the corruption that is occurring in ones nation.

“Well no country likes to be called corrupt, nobody likes to be called corrupt it’s a very triggering word. Comparing maybe let’s say Norway to Somalia might not get you very far, but I have found that countries react to its neighbors, regions and peers,” said Cohen.

“Canada falling behind say Germany or Britain, that matters to Canadians, because we see them as peers. So nobody wants to be at the bottom of the corruption index, everyone wants to move their way up and from there, hopefully it indicates a conversation amongst governments and citizens on how to move forward.”

“Businesses use the Corruption Perceptions Index to conduct risk reviews, about how to map out how to engage in certain countries, and hopefully it triggers people to reform for anti-corruption, and not become complacent about corruptions just the way things are done,” said Cohen.

He said the ranking and score level countries are placed at in the CPI, is important because it shows that countries have either stagnated their corruption ranking, or have worsened it throughout the years.

“The ranking, I think is to see where countries move between. The fact that Canada has fallen out of the top 10 and down to the 13 place, and we used to be at eighth place, there’s a trend line there to watch,” he said.

“We fell dramatically in 2019 and this year in 2021 and that got media coverage, but it’s been a gradual decline in our rank and in our overall score. These kind of trends should be indicators to the public and to politicians that they need to course correct.”

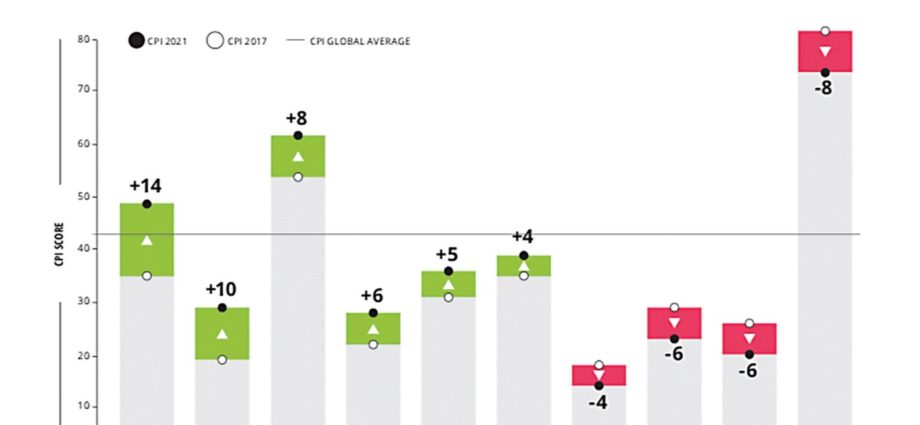

From the CPI index in 2017, Canada scored 82 and dropped to a score of 74, according to the 2021 CPI report. The full report can be found on the website of Transparency International, the global coalition against corruption.

What actions Canada has taken, based on CPI ranking

Cohen said the way a country would course correct their level of corruption, is based on a variety of factors.

“Well each country is unique on what they need to do to course correct on their situations,” Cohen said.

“In Canada, looking at the data that’s sent in to the CPI, Canada didn’t drop in ranking because of any specific issue it’s more of a ripple affect of the last couple years of headlines on ethics scandals, on Canada’s weak anti-money laundering, but also things like our access to information laws that have not been updated in a long time, people are finding it harder to conduct access to information searches. Our whistle-blower protection laws have not been updated either, those were both cited in some of the sourced material.”

“There’s been some movement on anti-money laundering in Canada, hopefully it continues, hopefully it gets bolstered. We’ve heard mentions from the RCMP that there are a number of cases being investigated on foreign bribery, hopefully we’ll see the results of that soon. On whistle-blower protection, we’ve had legislation that’s been endorsed across political parties at the federal level, but has not been passed.”

“The federal government conducted a review of our access to information laws and put out a ‘what we heard’ report, and we would like to see action on that.”

The theme of this year’s CPI report was corruption and human rights. According to Transparency International’s CPI, “corruption enables human rights abuses, setting off a vicious and escalating spiral. As rights and freedoms are eroded, democracy declines and authoritarianism takes its place, which in turn enables higher levels of corruption.”

Cohen said he hopes Canada can improve their ranking, based on the country’s placement in the CPI.

“As Transparency International Canada, our focus is on Canadian context. We hope there is continued momentum towards a publicly acceptable beneficial ownership registry,” he said.

“The federal government has pledged they will create one, so the provinces need to back it. Filling in additional gaps and loopholes in our anti-money laundering system. We want to see greater enforcement of the corruption of foreign public official acts, which we have been dismal about for years. We want to see expansion of our whistle-blower protection laws and updating to our access of information laws.”

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index can be found at https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2021