Kathy Walker, University of Saskatchewan and Susan Gingell, University of Saskatchewan

November 6, 2022

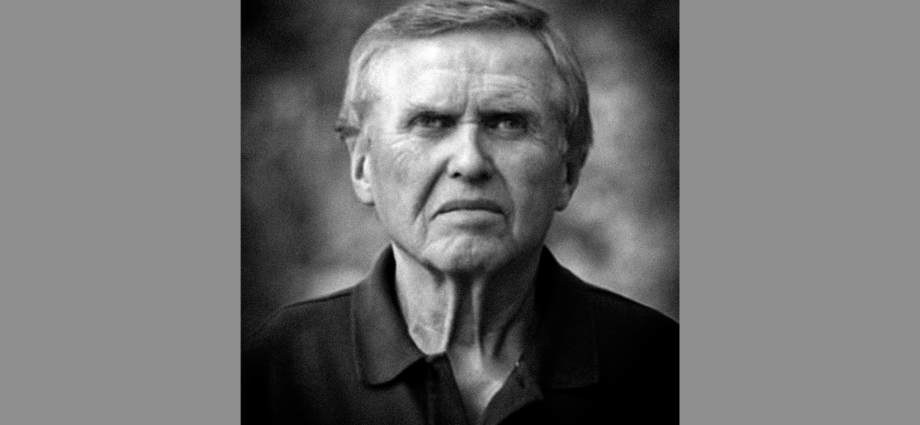

Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe and key legislators are under fire for inviting and initially defending the invitation of convicted killer and former cabinet minister Colin Thatcher to the throne speech.

The invitation was issued by Lyle Stewart, a Saskatchewan Party MLA and legislative secretary to the premier responsible for provincial economic autonomy.

Describing Thatcher as a “fine individual,” Stewart said: “If anybody has a right to be here, it’s Colin Thatcher.”

Stewart’s supposed “fine individual” is the same person who was convicted in 1984 of the first-degree murder of his ex-wife, JoAnn Wilson, in the garage of her Regina home. The pair was in a custody battle when Wilson was severely beaten before being shot in the skull.

It wasn’t the first time Wilson had been violently assaulted after the marriage breakdown. In 1981, she was shot in the shoulder through a patio door.

Longtime abuser

Thatcher’s final act of violence was, according to Wilson’s earlier statement, the culmination of abuses that experts — those who have lived and/or studied intimate partner violence — recognize as a classic escalation.

Under the influence of stress and alcohol, Thatcher reportedly pushed and kicked Wilson because she couldn’t soothe their sick infant and shoved her when she was nine months pregnant. Among several threats, he once said he would kill her and hide her body so it would never be found.

Yet when responding to questions about Thatcher’s invitation to the province’s throne speech, Christine Tell, minister of corrections, policing and public safety, said: “It doesn’t matter, he has a right to be here, just like anybody else. He is a free citizen.”

The comment implies that because Thatcher served a 22-year jail sentence before being released on parole, his crime is no longer relevant.

Moe has backpedalled on his initial refusal to apologize for the incident and reprimanded Stewart by removing him as his legislative secretary.

Tell, however, appears to have not suffered any political repercussions for her comments, though she admits her words were “inappropriate” and should not take away from the “horrendousness” of Thatcher’s “situation.”

Normalizing violence against women

To treat these reactions as the wrongful attitudes of a privileged few only compounds and masks what is really wrong with these responses. They illustrate that we live in a society that normalizes violence against women, and this normalization is reflected in systems that not only routinely fail to protect women from further violence, but also become the tools of abusers.

Saskatchewan, which has the highest rates (tied with Manitoba) of interpersonal family violence in Canada, according to the latest statistics, is a quintessential example. This kind of violence in Saskatchewan also rose between 2016 and 2019, so the problem is getting worse.

What does it say to those who have experienced or are experiencing such violence, when even the most horrific intimate partner violence is not enough to make a man a permanent pariah to the province’s most powerful politicians?

The Saskatchewan government should be just as concerned with the safety of domestic violence survivors as it currently is with asserting provincial autonomy.

Domestic violence survivors also require autonomy so they are not subject to violence in their own homes. The Saskatchewan Party’s version of autonomy is inherently patriarchal; we’d all benefit from measures that recognize women’s rights to a life free of violence and terror.

Survivors need resources

The same week Thatcher was being invited to the legislature, a forum was being held in Saskatoon called “Walking with Domestic Violence Survivors: Stories, Prevention, Responses and Healing.” It focused on the voices of survivors and those who work to support them.

An illusory autonomy is produced for domestic violence victims, typically women, when the onus is placed on them to protect themselves by moving away — despite widespread knowledge that the most dangerous period for victims is immediately after separation. As the speakers at the Saskatoon forum stated: “Why should the abused be the ones who lose their homes?” and “Where are they going to go?”

Survivors’ stories at the forum indicated that they need to be better connected with resources to help them heal. Saskatchewan currently does not provide operational funding to second-stage shelters that could provide security and counselling support.

Survivors also feel police frequently don’t believe them and do not provide adequate protection in an abuse situation. Social workers too often intervene by taking children from the abused parent on the grounds that they’re not providing a safe environment for their children. Family law courts do not take domestic violence into adequate account when determining custody of children.

English poet John Donne once remarked:

“Every [human] death diminishes me because I am involved in [Human]kind.”

The Saskatchewan government’s version of law and order would do well to recognize that Wilson’s death diminished us, and actively address its ongoing systemic causes and conditions — not accommodate and defend the supposed “rights” of her killer.

Kathy Walker, Assistant Professor, Department of Political Studies, University of Saskatchewan and Susan Gingell, Professor Emerita (Decolonizing & Women’s Literatures in English; Women’s and Gender Studies), University of Saskatchewan

Subscribe to our newsletter.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.