By Chadd Cawson, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, The Columbia Valley Pioneer

Sep 29, 2022

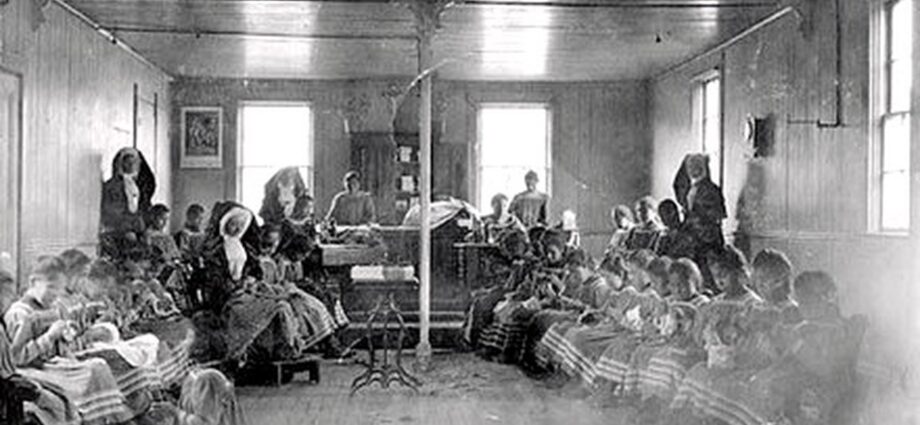

Many people have heard about residential schools but are uneducated about them. And too many have known about the horrors and injustices that happened within the walls of them, but for too long their voices were never heard. First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children were taken from their families, communities, and culture for over 150 years. During this period, over 150,000 children attended what were then called Indian Residential Schools. Many never returned home to their families.

Much of the country’s ignorance was their bliss until the 215 unmarked graves of children who attended the Kamloops Indian Residential School (KIRS) were uncovered in late May of 2021. KIRS was in operation from 1890 until its doors were finally closed in 1970. It took the uncovering of this tragedy and the many to follow, for eyes to finally open and ears to hear a truth that Indigenous people have been telling for years; a truth that could no longer be ignored.

While the first church-run residential school on record opened in 1831 it was 50 years later that the federal government adopted an official policy of funding residential schools across Canada, following the lead of a similar school system in the U.S. It was under John A. MacDonald who served as Prime Minister from 1867 to 1873 and again from 1878 to 1891, that a partnership between government and various church organizations such as the Catholic Church began. He was a man who has had monuments named after him and graced the Canadian ten-dollar bill for years. Yet he was responsible for the development of the residential school system and approving the execution of Métis leader, Louis Riel.

In 1894 Prime Minister Mackenzie Bowman made an amendment to the Indian Act which was first passed in 1876, that made it compulsory for all First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children to attend a residential or a day school which, like the name of latter suggests, demanded Indigenous children to attend during the day, allowing them to return home to their families afterwards. That aside, it did not make them any more pleasant to attend. Debra Fisher, the Regional Director for Métis Nation British Columbia, shared with the Pioneerthat her mother went to day school and would not talk of her experiences there. Fisher wears many hats: she’s the Minister of Education (K-12) and Early Years and Minister of Child and Family for Métis Nation British Columbia, and has spent five years working closely with residential and day school survivors of the Métis Nation.

“My mother never wanted to speak about her time in day school so that is a clear sign of how it impacted her,” said Fisher. “I have talked to many day school survivors and their experiences were vast – from not having any issues, aside from a poor education – to the full (impact) of residential schools such as sexual abuse and several forms of mistreatment.”

Many of our elders in the Columbia Valley of both the Ktunaxa First Nation and the Secwépemc (Shuswap) First Nation attended and endured abuse at St. Eugene’s residential school, located just north of Cranbrook. It opened in 1890 and didn’t finally close until 1970. The last federally-funded residential school was still open 25 years ago in Rankin Inlet and remained open until 1997.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

It was with intention that residential schools were located a great distance from Indigenous communities, making family visits few and far between. The whole purpose of this system was to strip young children of their culture, their languages, their way of life and their dignity. Young, innocent children endured physical and sexual abuse. Not all survived this sadistic system. The residential school system created, and leaves the legacy, of intergenerational trauma. That system left many who attended with the struggles of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance abuse and in extreme cases, suicide. The exact number of deaths that happened within residential schools is still unknown but are estimated to be over 30,000 and counting. The residential school system has since been considered a cultural genocide.